sea change (idiom): a complete transformation, a radical change of direction in attitude, goals . . . (Grammarist)

In my 53 years in the investment world, I’ve seen a number of economic cycles, pendulum swings, manias and panics, bubbles and crashes, but I remember only two real sea changes. I think we may be in the midst of a third one today.

As I’ve recounted many times in my memos, when I joined the investment management industry in 1969, many banks – like the one I worked for at the time – focused their equity portfolios on the so-called “Nifty Fifty.” The Nifty Fifty comprised the stocks of companies that were considered the best and fastest-growing – so good that nothing bad could ever happen to them. For these stocks, everyone was sure there was “no price too high.” But if you bought the Nifty Fifty when I started at the bank and held them until 1974, you were sitting on losses of more than 90% . . . from owning pieces of the best companies in America. Perceived quality, it turned out, wasn’t synonymous with safety or with successful investment.

Meanwhile, over in bond-land, a security with a rating of single-B was described by Moody’s as “failing to possess the characteristics of a desirable investment.” Non-investment grade bonds – those rated double-B and below – were off-limits to fiduciaries, since proper financial behavior mandated the avoidance of risk. For this reason, what soon became known as high yield bonds couldn’t be sold as new issues. But in the mid-1970s, Michael Milken and a few others had the idea that it should be possible to issue non-investment grade bonds – and to invest in them prudently – if the bonds offered enough interest to compensate for the risk of default. In 1978, I started investing in these securities – the bonds of perhaps America’s riskiest public companies – and I was making money steadily and safely.

In other words, whereas prudent bond investing had previously consisted of buying only presumedly safe investment grade bonds, investment managers could now prudently buy bonds of almost any quality as long as they were adequately compensated for the attendant risk. The U.S. high yield bond universe amounted to about $2 billion when I first got involved, and today it stands at roughly $1.2 trillion.

This clearly represented a major change in direction for the business of investing. But that’s not the end of it. Prior to the inception of high yield bond issuance, companies could only be acquired by larger firms – those that were able to pay with cash on hand or borrow large amounts of money and still retain their investment grade ratings. But with the ability to issue high yield bonds, smaller firms could now acquire larger ones by using heavy leverage, since there was no longer a need to possess or maintain an investment grade rating. This change permitted, in particular, the growth of leveraged buyouts and what’s now called the private equity industry.

However, the most important aspect of this change didn’t relate to high yield bonds, or to private equity, but rather to the adoption of anew investor mentality. Now risk wasn’t necessarily avoided, but rather considered relative to return and hopefully borne intelligently. This new risk/return mindset was critical in the development of many new types of investment, such as distressed debt, mortgage backed securities, structured credit, and private lending. It’s no exaggeration to say today’s investment world bears almost no resemblance to that of 50 years ago. Young people joining the industry today would likely be shocked to learn that, back then, investors didn’t think in risk/return terms. Now that’s all we do. Ergo, a sea change.

At roughly the same time, big changes were underway in the macroeconomic world. I think it all started with the OPEC oil embargo of 1973-74, which caused the price of a barrel of oil to jump from roughly $24 to almost $65 in less than a year. This spike raised the cost of many goods and ignited rapid inflation. Because the U.S. private sector in the 1970s was much more unionized than it is now and many collective bargaining agreements contained automatic cost-of-living adjustments, rising inflation triggered wage increases, which exacerbated inflation and led to yet more wage increases. This seemingly unstoppable upward spiral kindled strong inflationary expectations, which in many cases became self-fulfilling, as is their nature.

The year-over-year increase in the Consumer Price Index, which was 3.2% in 1972, rose to 11.0% by 1974, receded to the range of 6-9% for four years, and then rebounded to 11.4% in 1979 and 13.5% in 1980. There was great despair, as no relief was forthcoming from inflation-fighting tools ranging from WIN (“Whip Inflation Now”) buttons to price controls to a federal funds rate that reached 13% in 1974. It took the appointment of Paul Volcker as Fed chairman in 1979 and the determination he showed in raising the fed funds rate to 20% in 1980 to get inflation under control and extinguish inflationary psychology. As a result, inflation was back down to 3.2% by the end of 1983.

Volcker’s success in bringing inflation under control allowed the Fed to reduce the fed funds rate to the high single digits and keep it there over the rest of the 1980s, before dropping it to the mid-single digits in the ’90s. His actions ushered in a declining-interest-rate environment that prevailed for four decades(much more on this in the section that follows). I consider this the second sea change I’ve seen in my career.

The long-term decline in interest rates began just a few years after the advent of risk/return thinking, and I view the combination of the two as having given rise to (a) the rebirth of optimism among investors, (b) the pursuit of profit through aggressive investment vehicles, and (c) an incredible four decades for the stock market. The S&P 500 Index rose from a low of 102 in August 1982 to 4,796 at the beginning of 2022, for a compound annual return of 10.3% per year. What a period! There can be no greater financial and investment career luck than to have participated in it.

An Incredible Tailwind

What are the factors that gave rise to investors’ success over the last 40 years? We saw major contributions from (a) the economic growth and preeminence of the U.S.; (b) the incredible performance of our greatest companies; (c) gains in technology, productivity and management techniques; and (d) the benefits of globalization. However, I’d be surprised if 40 years of declining interest rates didn’t play the greatest role of all.

In the 1970s, I had a loan from a Chicago bank, with an interest rate of “three-quarters over prime.” (We don’t hear much about the prime rate anymore, but it was the benchmark interest rate – the predecessor of LIBOR – at which the money-center banks would lend to their best customers.) I received a notice from the bank each time my rate changed, and I framed the one that marked the high point in December 1980: It told me the interest rate on my loan had risen to 22.25%! Four decades later, I was able to borrow at just 2.25%, fixed for 10 years. This represented a decline of 2,000 basis points. Miraculous!

What are the effects of declining interest rates?

They accelerate the growth of the economy by making it cheaper for consumers to buy on credit and for companies to invest in facilities, equipment, and inventory.

They provide a subsidy to borrowers (at the expense of lenders and savers).

They reduce businesses’ cost of capital and thus increase their profitability.

They increase the fair value of assets. (The theoretical value of an asset is defined as the discounted present value of its future cash flows. The lower the discount rate, the higher the present value.) Thus, as interest rates fall, valuation parameters such as p/e ratios and enterprise values rise, and cap rates on real estate decline.

They reduce the prospective returns investors demand from investments they’re considering, thereby increasing the prices they’ll pay. This can be seen most directly in the bond market – everyone knows it’s “rates down; prices up” – but it works throughout the investment world.

By lifting asset prices, they create a “wealth effect” that makes people feel richer and thus more willing to spend.

Finally, by simultaneously increasing asset values and reducing borrowing costs, they produce a bonanza for those who buy assets using leverage.

I want to spend more time on that last point. Think about a buyer who employs leverage in a declining-rate environment:

He analyzes a company, concludes that he can make 10% a year on it, and decides to buy it.

Then he asks his head of capital markets how much it would cost to borrow 75% of the money. When he’s told it’s 8%, it’s full speed ahead. Earning 10% on three-quarters of the capital that’s borrowed at 8% would lever up the return on the other one-quarter (his equity) to 16%.

Banks compete to make the loan, and the result is an interest rate of 7% instead of 8%, making the investment even more profitable (a 19% levered return).

The interest cost on his floating-rate debt declines over time, and when his fixed-rate debt matures, he finds he can roll it over at 5%. Now the deal is a home run (a 25% levered return, all else being equal).

This narrative ignores the beneficial impact of declining interest rates on both the profitability of the company he bought and the market value of that company. Is it any wonder then that private equity and other levered strategies enjoyed great success over the last 40 years?

In a recent visit with clients, I came up with a bit of imagery to convey my view of the effect of the prolonged decline in interest rates: At some airports, there’s a moving walkway, and standing on it makes life easier for the weary traveler. But if rather than stand still on it, you walk at your normal pace, you move ahead rapidly. That’s because your rate of travel over the ground is the sum of the speed at which you’re walkingplusthe speed at which the walkway is moving.

That’s what I think happened to investors over the last 40 years. They enjoyed the growth of the economy and the companies they invested in, as well as the resulting increase in the value of their ownership stakes. But in addition, they were on a moving walkway, carried along by declining interest rates. The results have been great, but I doubt many people fully understand where they came from. It seems to me that a significant portion of all the money investors made over this period resulted from the tailwind generated by the massive drop in interest rates. I consider it nearly impossible to overstate the influence of declining rates over the last four decades.

The Recent Experience

The period between the end of the Global Financial Crisis in late 2009 and the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 was marked by ultra-low interest rates, and the macroeconomic environment – and its effects – were highly unusual.

An all-time low in interest rates was reached when the Fed cut the fed funds rate to approximately zero in late 2008 in an effort to pull the economy out of the GFC. The low rates were accompanied by quantitative easing: purchases of bonds undertaken by the Fed to inject liquidity into the economy (and perhaps to keep investors from panicking). The effects were dramatic:

The low rates and vast amounts of liquidity stimulated the economy and triggered explosive gains in the markets.

Strong economic growth and lower interest costs added to corporate profits.

Valuation parameters rose, as described above, lifting asset prices. Stocks increased non-stop for more than ten years, except for a handful of downdrafts that each lasted a few months. From a low of 667 in March 2009, the S&P 500 reached a high of 3,386 in February 2020, for a compound return of 16% per year.

The markets’ strength encouraged investors to drop their crisis-inspired risk aversion and return to risk taking much sooner than expected. It also made FOMO – the fear of missing out – the prevalent emotion among investors. Buyers were eager to buy, and holders weren’t motivated to sell.

Investors’ revived desire to buy caused the capital markets to reopen, making it cheap and easy for companies to obtain financing. Lenders’ eagerness to put money to work enabled borrowers to pay low interest rates under less-restrictive documentation that reduced lender protections.

The paltry yields on safe investments drove investors to buy riskier assets.

Thanks to economic growth and plentiful liquidity, there were few defaults and bankruptcies.

The main exogenous influences were increasing globalization and the limited extent of armed conflict around the world. Both influences were clearly salutary.

As a result, in this period, the U.S. enjoyed its longest economic recovery in history (albeit also one of its slowest) and its longest bull market, exceeding ten years in both cases.

When the Covid-19 pandemic caused much of the world’s economy to be shut down, the Fed dusted off the rescue plan that had taken months to formulate and implement during the GFC and put it into effect in a matter of weeks at a much larger scale than its earlier version. The U.S. government chipped in with loans and vast relief payments (on top of its customary deficit spending). The result in the period from March 2020 to the end of 2021 was a complete replay of the post-GFC developments enumerated above, including a quick economic bounce and an even quicker market recovery. (The S&P 500 rose from its low of 2,237 in March 2020 to 4,796 on the first day of 2022, up 114% in less than two years.)

For what felt like eons – from October 2012 to February 2020 – my standard presentation was titled “Investing in a Low Return World,” because that’s what our circumstances were. With the prospective returns on many asset classes – especially credit – at all-time lows, I enumerated the principal options available to investors:

invest as you previously have, and accept that your returns will be lower than they used to be;

reduce risk to prepare for a market correction, and accept a return that is lower still;

go to cash and earn a return of zero, hoping the market will decline and thus offer higher returns (and do it soon); or

ramp up your risk in pursuit of higher returns.

Each of these choices had serious flaws, and there’s a good reason for that. By definition, it’s hard to achieve good returns dependably and safely in a low-return world.

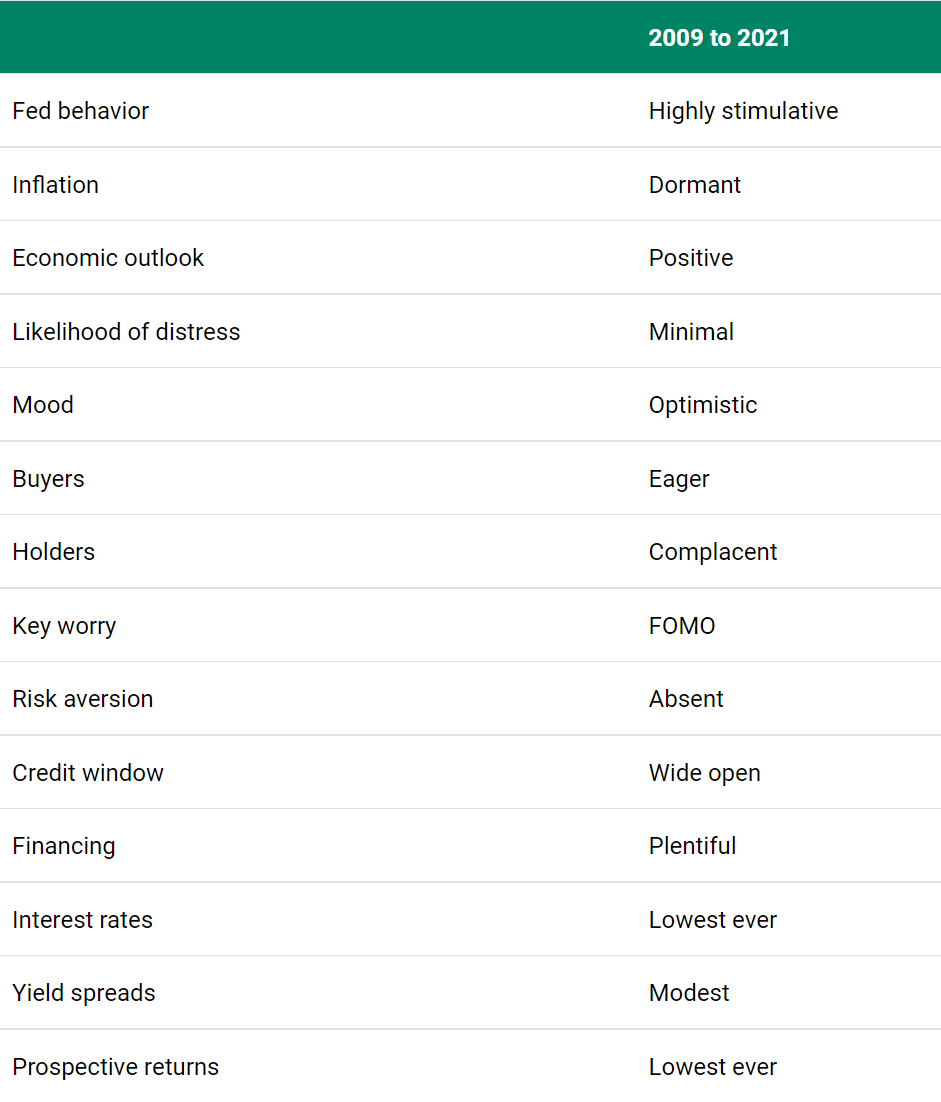

Regular readers of my memos know that my observations regarding the investment environment are primarily based on impressions and inferences rather than data. Thus, in recent meetings, I’ve been using the following list of properties to describe the period in question. (Think about whether you agree with this description. I’ll return to it later.)

The overall period from 2009 through 2021 (with the exception of a few months in 2020) was one in which optimism prevailed among investors and worry was minimal. Low inflation allowed central bankers to maintain generous monetary policies. These were golden times for corporations and asset owners thanks to good economic growth, cheap and easily accessible capital, and freedom from distress. This was an asset owner’s market and a borrower’s market. With the risk-free rate at zero, fear of loss absent, and people eager to make risky investments, it was a frustrating period for lenders and bargain hunters.

On recent visits with clients, I’ve been describing Oaktree as having spent the years 2009 through 2019 “in the wilderness” given our focus on credit and our heavy emphasis on value investing and risk control. To illustrate, after raising our largest fund up to that time in 2007-08 and putting most of it to work very successfully in the wake of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, we thought it appropriate, given the investment environment, to cut the amount in half for its successor fund and halve it again for the fund after that. Oaktree’s total assets under management grew relatively little during this period, and the returns on most of our closed-end funds, although fine, were moderate by our standards. It felt like a long slog.

That Was Then. This Is Now.

Of course, all of the above flipped in the last year or so. Most importantly, inflation began to rear its head in early 2021, when our emergence from isolation permitted too much money (savings amassed by people shut in at home, including distributions from massive Covid-19 relief programs) to chase too few goods and services (with supply hampered by the uneven restart of manufacturing and transportation). Because the Fed deemed the inflation “transitory,” it continued its policies of low interest rates and quantitative easing, keeping money loose. These policies further stimulated demand (especially for homes) at a time when it didn’t need stimulating.

Inflation worsened as 2021 wore on, and late in the year, the Fed acknowledged that it wasn’t likely to be short-lived. Thus, the Fed started reducing its purchases of bonds in November and began raising interest rates in March 2022, kicking off one of the quickest rate-hiking cycles on record. The stock market, which had ignored inflation and rising interest rates for most of 2021, began to fall around year-end.

From there, events followed a predictable course. As I wrote in the memo On the Couch (January 2016), whereas events in the real world fluctuate between “pretty good” and “not so hot,” investor sentiment often careens from “flawless” to “hopeless” as events that were previously viewed as benign come to be interpreted as catastrophic.

Higher interest rates led to higher demanded returns. Thus, stocks that had seemed fairly valued when interest rates were minimal fell to lower p/e ratios that were commensurate with higher rates.

Likewise, the massive increase in interest rates had its usual depressing effect on bond prices.

Falling stock and bond prices caused FOMO to dry up and fear of loss to replace it.

The markets’ decline gathered steam, and the things that had done best in 2020 and 2021 (tech, software, SPACs, and cryptocurrency) now did the worst, further dampening psychology.

Exogenous events have the ability to undercut the market’s mood, especially in tougher times, and in 2022 the biggest such event was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Ukraine conflict reduced supplies of grain and oil & gas, adding to inflationary pressures.

Since the tighter monetary policies were designed to slow the economy, investors focused on the difficulty the Fed would likely have achieving a soft landing, and thus the strong likelihood of a recession.

The anticipated effect of that recession on earnings dampened investors’ spirits. Thus, the fall of the S&P 500 over the first nine months of 2022 rivaled the greatest full-year declines of the last century. (It has now recovered a fair bit.)

The expectation of a recession also increased the fear of rising debt defaults.

New security issuance became difficult.

Having committed to fund buyouts in a lower-interest-rate environment, banks found themselves with many billions of dollars of “hung” bridge loans unsaleable at par. These loans have saddled the banks with big losses.

These hung loans forced banks to reduce the amounts they could commit to new deals, making it harder for buyers to finance acquisitions.

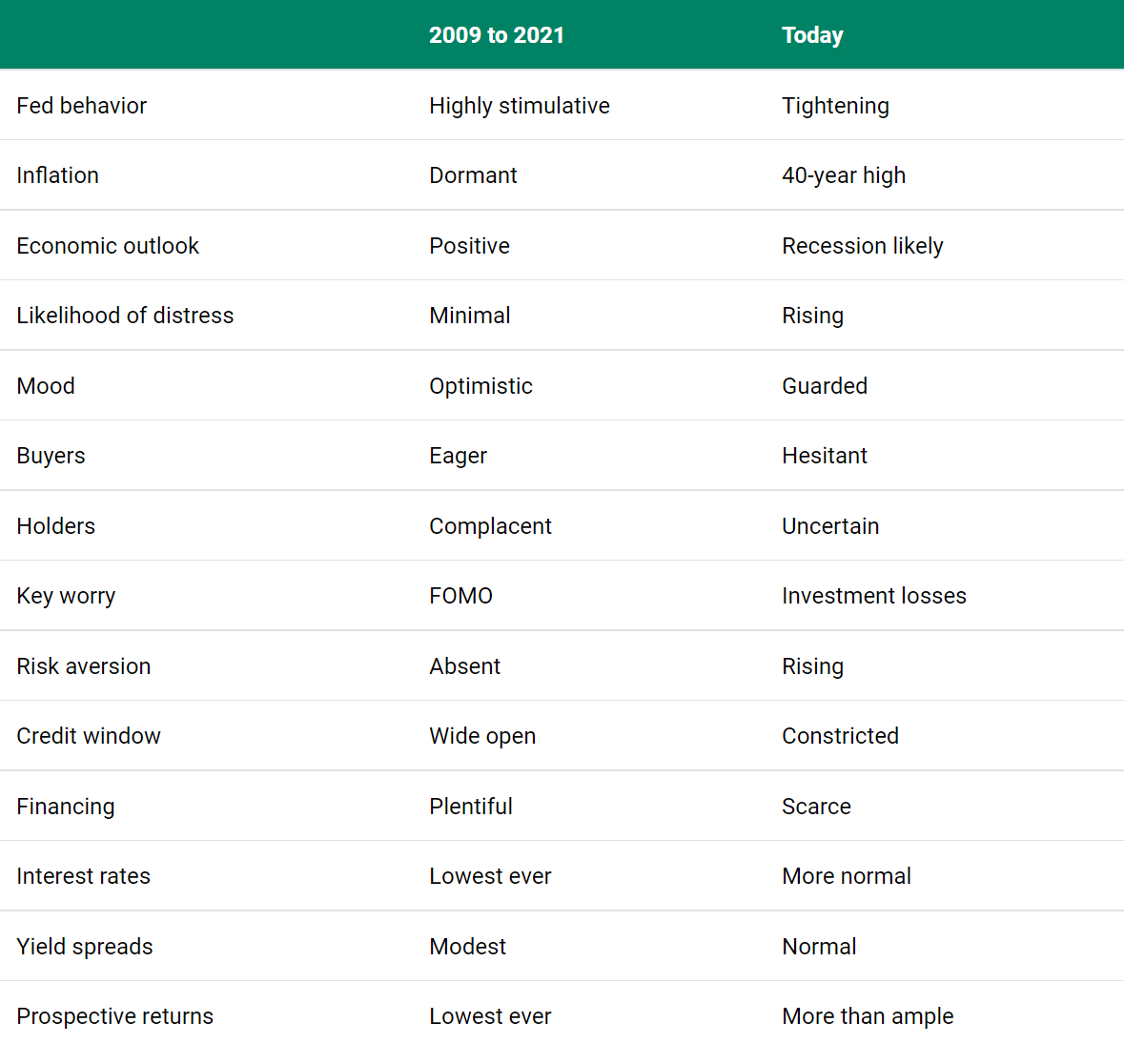

The progression of events described above caused pessimism to take over from optimism. The market characterized by easy money and upbeat borrowers and asset owners disappeared; now lenders and buyers held better cards. Credit investors became able to demand higher returns and better creditor protections. The list of candidates for distress – loans and bonds offering yield spreads of more than 1,000 basis points over Treasurys – grew from dozens to hundreds. Here’s how the change in the environment looks to me:

If the right-hand column accurately describes the new environment, as I believe it does, then we’re witnessing a complete reversal of the conditions in the middle column, which prevailed in 2021 and late 2020, throughout the 2009-19 period, and for much of the last 40 years.

How has this change manifested itself in investment options? Here’s one example: In the low-return world of just one year ago, high yield bonds offered yields of 4-5%. A lot of issuance was at yields in the 3s, and at least one new bond came to the market with a “handle” of 2. The usefulness of these bonds for institutions needing returns of 6 or 7% was quite limited. Today these securities yield roughly 8%, meaning even after allowing for some defaults, they’re likely to deliver equity-like returns, sourced from contractual cash flows on public securities. Credit instruments of all kinds are potentially poised to deliver performance that can help investors accomplish their goals.

The Outlook

Inflation and interest rates are highly likely to remain the dominant considerations influencing the investment environment for the next several years. While history shows that no one can predict inflation, it seems likely to remain higher than what we became used to after the GFC, at least for a while. The course of interest rates will largely be determined by the Fed’s progress in bringing inflation under control. If rates go much higher in that process, they’re likely to come back down afterward, but no one can predict the timing or the extent of the decrease.

While everyone knows how little I think of macro forecasts, a number of clients have asked recently about my views regarding the future of interest rates. Thus, I’ll provide a brief overview. (Oaktree’s investment philosophy doesn’t prohibit having opinions, just acting as if they’re right.) In my view, the buyers who’ve driven the S&P 500’s recent 10% rally from the October low have been motivated by their beliefs that (a) inflation is easing, (b) the Fed will soon pivot from restrictive policy back toward stimulative, (c) interest rates will return to lower levels, (d) a recession will be averted, or it will be modest and brief, and (e) the economy and markets will return to halcyon days.

In contrast, here’s what I think:

The underlying causes of today’s inflation will probably abate as relief-swollen savings are spent and as supply catches up with demand.

While some recent inflation readings have been encouraging in this regard, the labor market is still very tight, wages are rising, and the economy is growing strongly.

Globalization is slowing or reversing. If this trend continues, we will lose its significant deflationary influence. (Importantly, consumer durables prices declined by 40% over the years 1995-2020, no doubt thanks to less-expensive imports. I estimate that this took 0.6% per year off the rate of inflation.)

Before declaring victory on inflation, the Fed will need to be convinced not only that inflation has settled near the 2% target, but also that inflationary psychology has been extinguished. To accomplish this, the Fed will likely want to see a positive real fed funds rate – at present it’s minus 2.2%.

Thus, while the Fed appears likely to slow the pace of its interest rate increases, it’s unlikely to return to stimulative policies any time soon.

The Fed has to maintain credibility (or regain it after having claimed for too long that inflation was “transitory”). It can’t appear to be inconstant by becoming stimulative too soon after having turned restrictive.

The Fed faces the question of what to do about its balance sheet, which grew from $4 trillion to almost $9 trillion due to its purchases of bonds. Allowing its holdings of bonds to mature and roll off (or, somewhat less likely, making sales) would withdraw significant liquidity from the economy, restricting growth.

Rather than be in a stimulative posture on a perpetual basis, one might imagine the Fed would prefer to normally maintain a “neutral interest rate,” which is defined as neither stimulative nor restrictive. (I know I would.) Most recently – last summer – that rate was estimated at 2.5%.

Similarly, although most of us believe the free market is the best allocator of economic resources, we haven’t had a free market in money for well over a decade. The Fed might prefer to reduce its role in capital allocation by being less active in controlling rates and holding mortgage bonds.

There must be risks associated with the Fed keeping interest rates stimulative on a long-term basis. Arguably, we’ve seen most recently that doing so can bring on inflation, though the inflation of the last two years can be attributed largely to one-off events related to the pandemic.

The Fed would probably like to see normal interest rates high enough to provide it with room to cut if it needs to stimulate the economy in the future.

People who came into the business world after 2008 – or veteran investors with short memories – might think of today’s interest rates as elevated. But they’re not in the longer sweep of history, meaning there’s no obvious reason why they should be lower.

These are the reasons why I believe that the base interest rate over the next several years is more likely to average 2-4% (i.e., not far from where it is now) than 0-2%. Of course, there are counterarguments. But, for me, the bottom line is that highly stimulative rates are likely not in the cards for the next several years, barring a serious recession from which we need rescuing (and that would have ramifications of its own). But I assure you Oaktree isn’t going to bet money on that belief.

What we do know is that inflation and interest rates are higher today than they’ve been for 40 and 13 years, respectively. No one knows how long the items in the right-hand column above will continue to accurately describe the environment. They’ll be influenced by economic growth, inflation, and interest rates, as well as exogenous events, all of which are unpredictable. Regardless, I think things will generally be less rosy in the years immediately ahead:

A recession in the next 12-18 months appears to be a foregone conclusion among economists and investors.

That recession is likely to coincide with deterioration of corporate earnings and investor psychology.

Credit market conditions for new financings seem unlikely to soon become as accommodative as they were in recent years.

No one can foretell how high the debt default rate will rise or how long it’ll stay there. It’s worth noting in this context that the annual default rate on high yield bonds averaged 3.6% from 1978 through 2009, but an unusually low 2.1% under the “just-right” conditions that prevailed for the decade 2010-19. In fact, there was only one year in that decade in which defaults reached the historical average.

Lastly, there is a forecast I’m confident of: Interest rates aren’t about to decline by another 2,000 basis points from here.

As I’ve written many times about the economy and markets, we never know where we’re going, but we ought to know where we are. The bottom line for me is that, in many ways, conditions at this moment are overwhelmingly different from – and mostly less favorable than – those of the post-GFC climate described above. These changes may be long-lasting, or they may wear off over time. But in my view, we’re unlikely to quickly see the same optimism and ease that marked the post-GFC period.

We’ve gone from the low-return world of 2009-21 to a full-return world, and it may become more so in the near term. Investors can now potentially get solid returns from credit instruments, meaning they no longer have to rely as heavily on riskier investments to achieve their overall return targets. Lenders and bargain hunters face much better prospects in this changed environment than they did in 2009-21. And importantly, if you grant that the environment is and may continue to be very different from what it was over the last 13 years – and most of the last 40 years – it should follow that the investment strategies that worked best over those periods may not be the ones that outperform in the years ahead.

That’s the sea change I’m talking about.

December 13, 2022

Howard Stanley Marks (born April 23, 1946) is an American investor and writer. He is the co-founder and co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, the largest investor in distressed securities worldwide. In 2022, with a net worth of $2.2 billion, Marks was ranked No. 1365 on the Forbes list of billionaires.

Marks is admired in the investment community for his "memos", which detail his investment strategies and insight into the economy and are posted publicly on the Oaktree website. He has also published 3 books on investing. According to Warren Buffett, "When I see memos from Howard Marks in my mail, they're the first thing I open and read. I always learn something, and that goes double for his book."

Comments