The U.S. economy has experienced 12 recessions since World War II, and each one included two features: Economic output contracted and unemployment rose.

Today, something highly unusual is happening. Economic output fell in the first quarter and signs suggest it did so again in the second. Yet the job market showed little sign of faltering during the first half of the year. The jobless rate fell from 4% last December to 3.6% in May.

It is the latest strange twist in the odd trajectory of the pandemic economy, and a riddle for those contemplating a recession. If the U.S. is in or near one, it doesn't yet look like any other on record.

Analysts sometimes talked about "jobless recoveries" after past recessions, in which economic output rose but employers kept shedding workers. The first half of 2022 was the mirror image -- a "jobful" downturn, in which output fell and companies kept hiring. Whether it will spiral into a fuller and deeper recession isn't known, though a growing number of economists believe it will.

Some companies, especially in the tech sector, have given indications that they're pulling back on hiring, though across the broad economy the job market has rarely looked stronger.

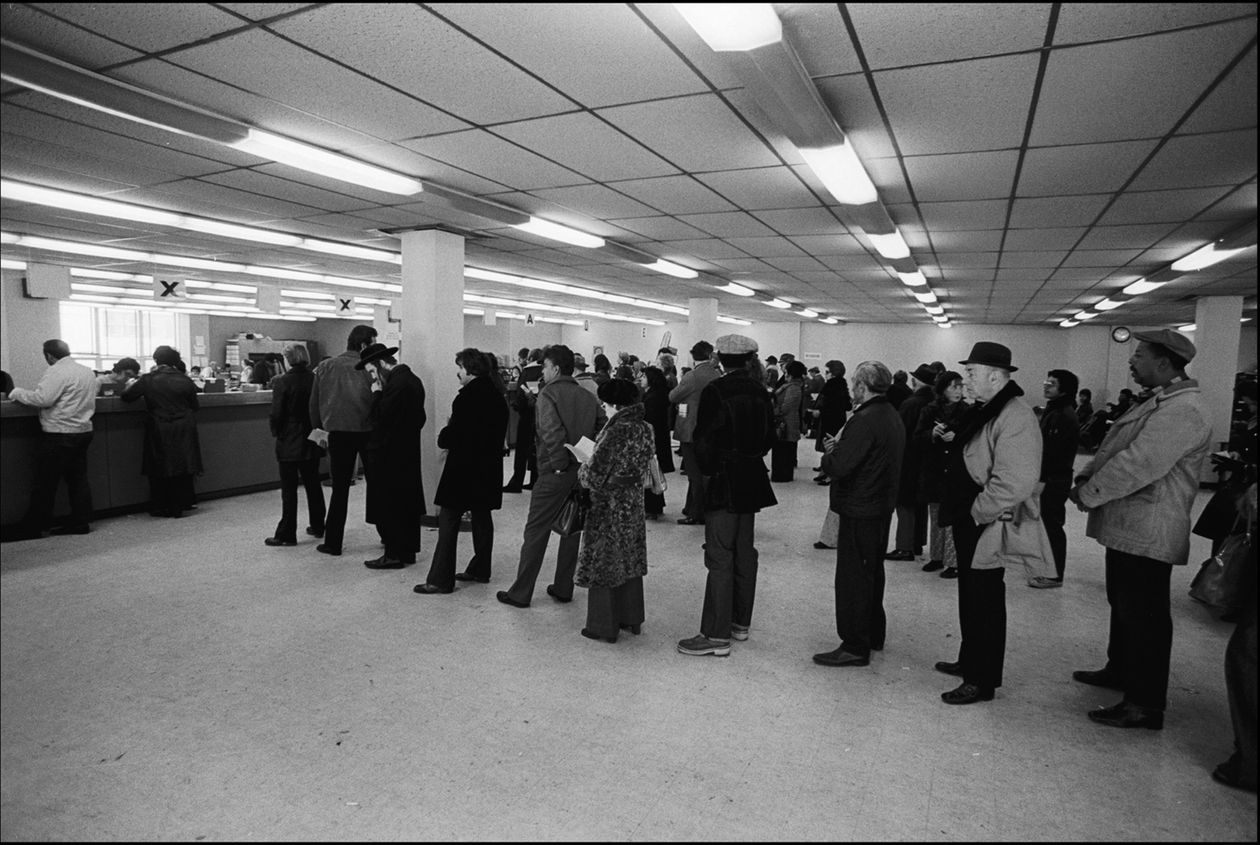

At the end of June, 1.3 million Americans were collecting federal unemployment checks, substantially fewer than the 1.7 million people collecting them on average each week during the three years before the pandemic, when the economy was considered to be exceptionally strong. The number of people receiving such benefits topped 6.5 million during the 2007-09 recession and exceeded 3 million during the two earlier downturns.

"I would be surprised if there were a recession without much job loss," said Gregory Mankiw, a Harvard University economics professor. He said if one is coming, it would likely be provoked by Federal Reserve interest rate increases. A "small downturn" could be needed to bring inflation under control, he said.

The official arbiter of U.S. recessions is the National Bureau of Economic Research, a collection of mostly academic economists who place dates on when recessions begin and end, going back to 1857, the first U.S. recession on record. Mr. Mankiw served on the committee during the 1990s.

One popular rule of thumb is that the economy is in recession when gross domestic product -- a measure of the nation's output of goods and services -- contracts for two consecutive quarters, but that's not the way the NBER sees it. Its eight-member business cycle dating committee looks at a range of monthly and quarterly indicators, including output, income, manufacturing activity, business sales and, perhaps most important, employment levels. Then it makes a judgment call.

"A recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, normally visible in production, employment, and other indicators," the committee says.

The indicators don't always move in sync. In 2001, output didn't decline much, and GDP didn't contract for two consecutive quarters, but the NBER called it a recession, anyway. In 1960, inflation-adjusted household income rose, and that was a recession, too.

One common denominator has been jobs. The unemployment rate has increased every time, by as little as 1.9 percentage points in 1960 and 1961 and as much as 11.2 percentage points in 2020. The median increase in the jobless rate among all 12 post-World War II recessions was 3.5 percentage points. The U.S. didn't escape any of those recessions with a jobless rate below 6.1%.

Monthly business payrolls, watched closely by the NBER, also have fallen in every recession, by about 3% in a typical one. Yet between December and May, payrolls rose 2.4 million, or 1.6%. They are a coincident indicator, meaning they tend to rise and fall in sync with broad economic activity.

On Friday the Labor Department will report nationwide figures for payrolls and unemployment for June, a potentially critical moment in the recession debate. Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal in advance of the report said they expected the Labor Department to report that the jobless rate held steady at 3.6% last month and payrolls kept expanding.

The backdrop to U.S. jobs is now unusual. The U.S. has recorded more than 11 million unfilled job openings in six of the past seven months, four million more monthly openings than was typical before Covid-19 hit the economy in early 2020. In other words, demand for workers is abundant.

At the same time, labor is scarce -- in part because baby boomers are retiring -- making firms reluctant to fire the workers they have. The size of the labor force, at 164.4 million in May, was still slightly smaller than the 164.6 million people who were working or looking for work right before the pandemic, so even when people do lose work, there have been many unfilled positions available.

Robert Gordon, a Northwestern University economics professor and member of the NBER's business cycle dating committee, said this might be a situation in which other indicators point to recession but the job market doesn't, or it lags behind atypically for several months.

"We are going to have a very unusual conflict between the employment numbers and the output numbers for a while," he said. Some other meaningful indicators, such as manufacturing and wholesaler sales, have also weakened, he added, making him wary that a recession is near. He noted he wasn't speaking for the committee or any decisions it might make.

Even the most pessimistic economists see a modest jobs downturn in the months ahead.

About two in five economists surveyed by the Journal in June said they saw at least a 50-50 chance that the U.S. enters recession in the coming year, but among them, few saw a big increase in the jobless rate. They forecast a 3.9% unemployment rate at the end of this year and a 4.6% unemployment rate at the end of 2023. The U.S. has never had a recession in the post-World War II era with a jobless rate that low.

"The U.S. is in, or on the precipice, of a shallow but yearlong recession. This will assist the Fed in its inflation fighting efforts," said Sean Snaith, director of the University of Central Florida's Institute for Economic Forecasting, in the Journal's survey. He sees the jobless rate rising to 6% by the end of 2023, the only person in the survey who saw the rate reaching that level in the next 18 months.

History shows that recessions come in many forms.

Some downturns have been long and deep, such as the downturn of 2007-09 that sent the unemployment rate to 10%; others short and shallow, such as the 2001 recession that lasted eight months. Others were part of serial downturns, as happened in the 1950s and 1980s, when recessions came in succession, a short time apart.

"Each recession seems to have a different driving force and different duration and impact on jobs and output," said Peter Klenow, a Stanford University economics professor. "I think of the 1980 recession as Carter credit controls, 1981-1982 as the Volcker recession, 1990-1991 as a credit crunch, 2001 the bursting of the dot-com bubble, 2008-2009 the global financial crisis, and 2020 the pandemic recession."

The 2020 recession, in particular, was unlike anything recorded in U.S. history, exceptionally short at just two months, and exceptionally severe. Companies cut 22 million jobs in those two months, 14 times more than they had ever cut in a two-month period during the post-Depression era.

This was a precursor to the turbulence still hitting the economy more than two years later, like waves in a lake after a boulder falls in.

Officials in Washington reacted to the Covid shock by flooding the economy with stimulus and boosting demand. Supply chains broke down, in part because of Covid-related business closures around the world. The surge of demand and the collapse of supply then bred higher inflation. The Fed is now trying to slow it by raising short-term interest rates to restrain demand for interest-sensitive spending, such as on cars, homes and business projects.

What happened in the first part of the year in part reflected volatility in the economy that followed Covid, compounded by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Businesses drew down inventories in the first quarter after building them up in 2021, according to Commerce Department data. The U.S. trade position also deteriorated, meaning fewer exports and more imports.

The inventory reductions were central to a contraction in gross domestic product at a 1.6% annual rate in the first quarter. Rather than build new cars or computer chips, companies took them off their own shelves.

A Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta model closely watched on Wall Street estimates that economic output contracted again in the second quarter, at a 2.1% annual rate. The model puts inventory reductions as the biggest downward weight on output.

Inventories are a business buffer for surprises, and cycles of inventory building and destocking have been common ingredients in the early stages of past recessions. Firms at times produce too much in anticipation of demand and then have to pull back when the demand doesn't materialize. In past cycles, production declines associated with inventory reductions set off a series of events that caused recessions, including layoffs, household income loss and then slowing consumer spending.

One risk now is that inventory cutting leads to wider business retrenchment that feeds on itself, as happened in some past recessions.

Another uncertainty is the outlook for home building, which is highly interest rate sensitive and has been another leading indicator during past downturns. New-home construction dropped 14% in May from a month earlier, seasonally adjusted, a drag that could persist as the Fed raises short-term interest rates.

Most post-World War II recessions have been associated with declines in residential home construction, though the hit this time may not be severe because building wasn’t as overheated in recent years as it had been in the past. For example, in the first quarter, total U.S. spending on home-building was still 22% below the pace of building at the peak of the housing boom of the early 2000s, according to Commerce Department data.

Bruce Kasman, chief economist at J.P. Morgan, predicts a “bend-but-don’t-break” scenario for the economy, meaning a sharp slowdown in activity that doesn’t crack the job market. However, he adds that he doesn’t have great conviction about that prediction, given the unusual backdrop and the shocks that keep hitting the economy.

Though corporate profits are slowing, he said, corporate profit margins are exceptionally high, historically. At around 18% of sales during the past year, after-tax profits have rarely been higher in post-World War II history. Heading into recessions in 1991 and 2001, firm profit margins had fallen to single digit levels. Firms cut back on spending to build profits, and dragged the economy down in the process.

Mr. Kasman said firms now have a large cushion to the growing profit slowdown. Businesses are also swimming in nearly $4 trillion of cash, a record, he said, and another cushion.

Slow growth and continued hiring would add up to productivity and profit pressures for many businesses. That would be bad news for stocks, he said. But a recession? He’s not counting on it.

Households are flush with cash, too. At the end of the first quarter, they had $18.5 trillion in checking accounts, savings accounts and money market mutual funds, according to Fed data. That was up from $13.3 trillion before the pandemic, boosted in part by several rounds of relief checks sent to households in the past two years.

Comments