Index of banks posts biggest drop since pandemic roiled markets nearly three years ago

Investors dumped shares of SVB Financial Group and a swath of U.S. banks after the tech-focused lender said it lost nearly $2 billion selling assets following a larger-than-expected decline in deposits.

The four biggest U.S. banks lost $52 billion in market value Thursday. The KBW Nasdaq Bank Index notched its biggest decline since the pandemic roiled the markets nearly three years ago. Shares of SVB, the parent of Silicon Valley Bank, fell more than 60% after it disclosed the loss and sought to raise $2.25 billion in fresh capital by selling new shares.

Banks big and small posted steep declines. PacWest Bancorp fell 25%, and First Republic Bank lost 17%. Charles Schwab Corp. fell 13%, while U.S. Bancorp lost 7%. America’s biggest bank, JPMorgan Chase& Co., fell 5.4%.

Thursday’s rout is another consequence of the Federal Reserve’s aggressive campaign to control inflation. Rising interest rates have caused the value of existing bonds with lower payouts to fall in value. Banks own a lot of those bonds, including Treasurys, and are now sitting on giant unrealized losses.

Large declines in value aren’t necessarily a problem for banks unless they are forced to sell the assets to cover deposit withdrawals. Most banks aren’t doing so, even though their customers are starting to move their deposits into higher-yielding alternatives. Yet a few banks have run into trouble this week, sparking fears that other banks could be forced to take losses to raise cash.

SVB said late Wednesday it would book a $1.8 billion after-tax loss on sales of investments and seek to raise $2.25 billion by selling a mix of common and preferred stock.

The bank’s assets and deposits almost doubled in 2021, large amounts of which SVB poured into U.S. Treasurys and other government-sponsored debt securities. Soon after, the Fed began raising rates. That battered the tech startups and venture-capital firms Silicon Valley Bank serves, sparking a faster-than-expected decline in deposits that continues to gain steam.

Some venture-capital investors have advised startups to pull their money out of SVB, citing liquidity concerns, according to people familiar with the matter.

Garry Tan, president of the startup incubator Y Combinator, posted this internal message to founders in the program: “We have no specific knowledge of what’s happening at SVB. But anytime you hear problems of solvency in any bank, and it can be deemed credible, you should take it seriously and prioritize the interests of your startup by not exposing yourself to more than $250K of exposure there. As always, your startup dies when you run out of money for whatever reason.”

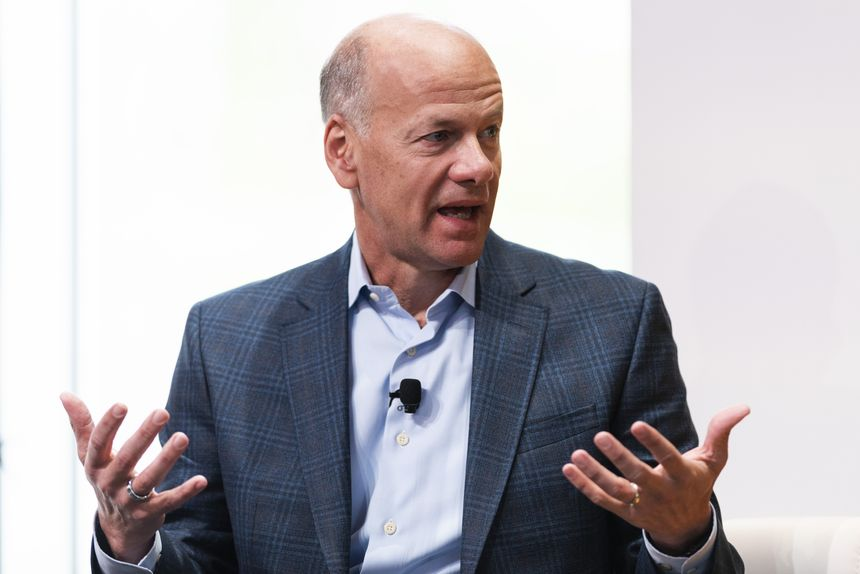

SVB Chief ExecutiveGreg Beckerheld a call Thursday trying to reassure customers about the bank’s financial health, according to people familiar with the matter. Mr. Becker urged them not to pull their deposits from the bank and not to spread fear or panic about its situation, the people said.

The collapse of Silvergate Capital Corp., one of the crypto market’s top banks, is a more extreme example of deposit flight. The California bank said Wednesday it would shut down after the crypto meltdown sparked a deposit run that forced it to sell billions of dollars of assets at a steep loss.

“This is the first sign there might be some kind of crack in the financial system,” said Bill Smead, chairman and chief investment officer of Smead Capital Management, a $5.5 billion firm that counts Bank of America Corp. and JPMorgan among its holdings. “People are waking up to the gravity that this was one of the biggest financial euphoria episodes.”

Banks don’t incur losses on their bond portfolios if they are able to hold on to them until maturity. But if they suddenly have to sell the bonds at a loss to raise cash, that is when accounting rules require them to show the realized losses in their earnings.

Those rules let companies exclude losses on their bonds from earnings if they classify the investments as “available for sale” or “held to maturity.”

Sometimes the losses catch investors by surprise, even if the problem has been slowly building and fully disclosed for a long time.

At SVB, unrealized losses had been piling up throughout last year and were visible to anyone reading its financial reports.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. in February reported that U.S. banks’ unrealized losses on available-for-sale and held-to-maturity securities totaled $620 billion as of Dec. 31, up from $8 billion a year earlier before the Fed’s rate push began.

In part, U.S. banks are suffering the aftereffects of a Covid-era deposit boom that left them awash in cash that they needed to put to work. Domestic deposits at federally insured banks rose 38% from the end of 2019 to the end of 2021, FDIC data show. Over the same period, total loans rose 7%, leaving many institutions with large amounts of cash to deploy in securities as interest rates were near record lows.

U.S. commercial banks’ holdings of U.S. government securities surged 53% over the same period, to $4.58 trillion, according to Fed data.

Most of the unrealized investment losses in the banking system are at the largest lenders. In its annual report, Bank of America said the fair-market value of its held-to-maturity debt securities was $524 billion as of Dec. 31, 2022, $109 billion less than the value it showed for them on its balance sheet.

Bank of America and its megabank peers can afford to part with a lot of deposits before they are forced to crystallize those losses.

Most of SVB’s liabilities—89% at the end of 2022—are deposits. Bank of America draws its funding from a much wider set of sources that includes more long-term borrowing; 69% of its liabilities are deposits.

And, unlike SVB and Silvergate, big banks hold a range of assets and serve companies across the economy, minimizing the risk that a downturn in any one industry will cause them serious harm.

“On the other hand, unrealized losses weaken a bank’s future ability to meet unexpected liquidity needs,” FDIC ChairmanMartin Gruenbergsaid in a March 6 speech.

The risks are most acute for small lenders. Smaller banks must often pay higher deposit rates to attract customers than megabanks with flashy technology and extensive branch networks. Bank of America paid an average rate of 0.96% on deposits in the fourth quarter, compared with 1.17% for the industry. SVB paid 2.33%.

SVB, based in Santa Clara, Calif., caters to tech, venture-capital and private-equity firms and grew rapidly along with those industries. Total deposits rose 86% in 2021 to $189 billion and peaked at $198 billion a quarter later.

They fell 13% during the final three quarters of 2022 and continued dropping in January and February “in part because of its concentration in investor-funded technology company deposits and the slowdown in public and private investments over the past year,” Standard & Poor’s credit analysts wrote in a note downgrading SVB to one notch above junk. They said they expect SVB’s deposits might decline further.

SVB’s debt securities declined in value substantially last year. As of Dec. 31, SVB’s balance sheet showed securities labeled “available for sale” that had a fair market value of $26.1 billion, $2.5 billion below their $28.6 billion cost. Under accounting rules, the available-for-sale label allowed SVB to exclude the paper losses on those holdings from its earnings, although the losses did count in equity.

In a news release Wednesday, SVB said it had sold substantially all of its available-for-sale securities. The company said it decided to sell the holdings and raise fresh capital “because we expect continued higher interest rates, pressured public and private markets, and elevated cash-burn levels from our clients as they invest in their businesses.”

SVB’s year-end balance sheet also showed $91.3 billion of securities that it classified as “held to maturity.” That label allows SVB to exclude paper losses on those holdings from both its earnings and equity.

In a footnote to its latest financial statements, SVB said the fair-market value of those held-to-maturity securities was $76.2 billion, or $15.1 billion below their balance-sheet value. The fair-value gap at year-end was almost as large as SVB’s $16.3 billion of total equity.

SVB hasn’t wavered from its position that it intends to hold those bonds to maturity. Most of the held-to-maturity securities consisted of mortgage bonds issued by government-sponsored entities, such as Fannie Mae, which have no risk of default.

They do present market risk, including interest-rate risk, because bond values fall when rates rise. The yield on two-year Treasurys recently topped 5%, up from 4.43% at the end of 2022.

Some investors got a nice payday in Thursday’s plunge. Some 5.4% of SVB’s available shares were sold short, according to FactSet data from last month. Short sellers aim to profit by borrowing and selling shares of companies they believe are overvalued, then buying them back later at a lower price.

Far fewer investors were betting against the tech-focused lender’s peers. Last month short interest was 2% at Fifth Third Bancorp, 1.4% at State Street Corp. and 1% at American Express Co.

Comments