Oil-and-gas companies have built up a mountain of cash with few precedents in recent history. Wall Street has a few ideas on how to spend it -- and new drilling isn't near the top of the list.

Many companies are cutting costs and raining cash on stock pickers like Berkshire Hathaway's Warren Buffett, who believe the world's thirst for oil will continue for years, if not decades, to come. The promise of money returned to shareholders helped turn energy shares into some of the few bright spots in a dark moment for markets last year, fueled by commodity prices that skyrocketed after Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

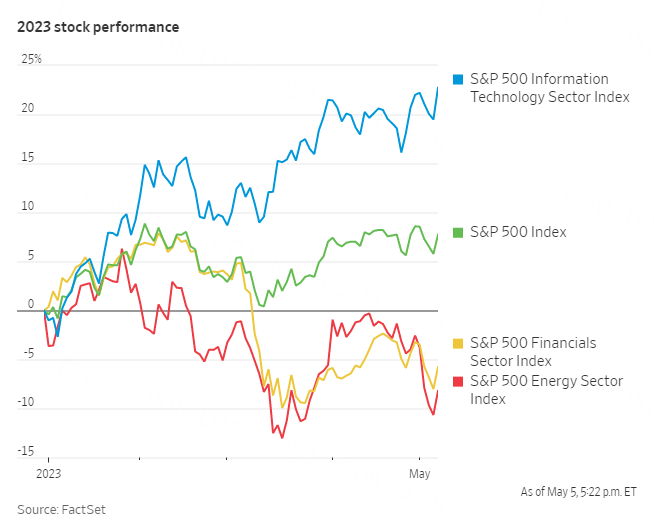

Even as an uncertain economic outlook has weighed on crude in 2023, making the energy sector the S&P 500's worst performer, cash has continued flowing. Companies that previously chased growth and funneled money into speculative drilling investments, weighing down their stocks, have instead tried to appease Wall Street by boosting dividends and repurchasing shares.

The cash has helped make up for stock prices that often seesaw alongside volatile commodity markets. Steady returns also buoy an industry with an uncertain long-term outlook as governments, markets and the global economy gradually shift toward cleaner energy.

"They've paid dividends forever. That's been a hallmark," said Rob Thummel, managing director at Tortoise, an energy investment firm. "But now there's excess cash beyond dividends to do buybacks."

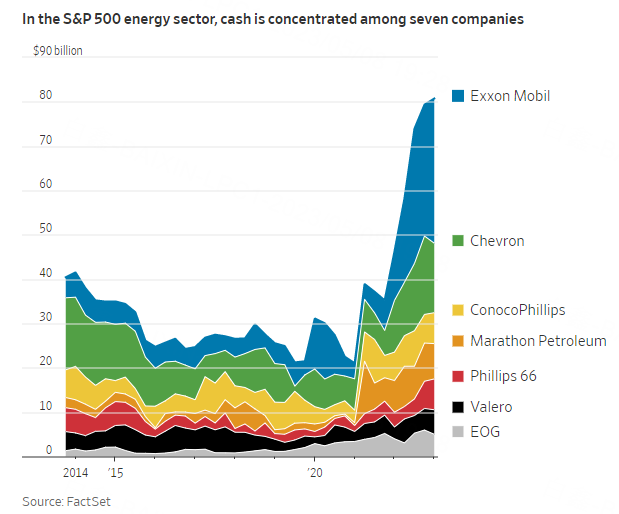

Six companies often described as Big Oil -- Italy's Eni, France's TotalEnergies, the U.K.'s Shell and BP, and domestically headquartered Chevron and Exxon Mobil -- reported nearly $160 billion in cash and cash equivalents across their balance sheets at the end of the first quarter. State-owned companies and smaller businesses have tens of billions more.

Chevron and Exxon Mobil hold $48.3 billion of such assets, up $1 billion from the beginning of the year, according to FactSet. Before the cash pileup in recent months, the last time they collectively surpassed $40 billion was in the final weeks of George W. Bush's presidency as U.S. crude neared the end of a monthslong retreat from a record $145 a barrel.

Oil profits last year ballooned after Russia's war on Ukraine pushed up prices and turned gasoline into a street-level reminder that inflation neared 40-year highs. As benchmark U.S. crude prices have dropped 11% this year, to $71.34 a barrel, international oil majors, U.S. fuel-makers, independent drillers, Texas wildcatters and Appalachian frackers have kept gobs of cash on hand -- partially as insurance if the slide continues.

"We know the good times don't last," Chevron Chief Financial Officer Pierre Breber told analysts in an earnings call.

President Biden has called on producers to ramp up output in a bid to lower prices at the pump. "These balance sheets make clear that there is nothing stopping oil companies from boosting production except their own decision to pad wealthy shareholder pockets and then sit on whatever is left," White House Assistant Press Secretary Abdullah Hasan said.

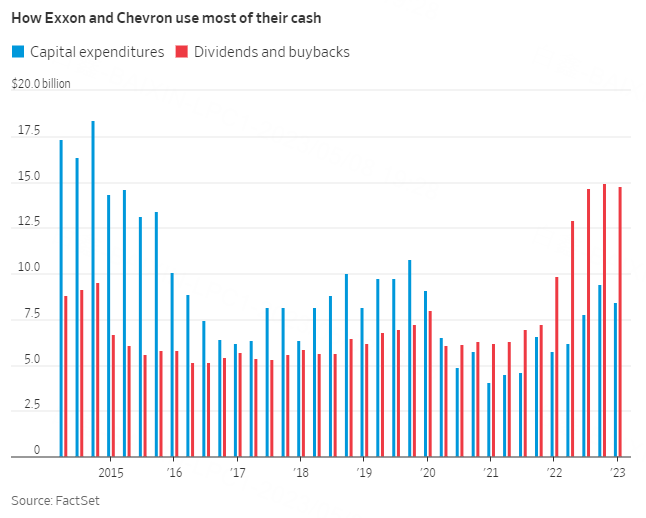

But investors have favored financial discipline, and executives are increasingly compensated based on shareholder returns. It marks an about-face in the U.S. oil patch, where companies for years chased production growth by tapping gushers of crude in regions such as the Permian Basin in Texas and Bakken shale in North Dakota.

By June 2020, as the pandemic brought parts of the country to a standstill, Chevron and Exxon Mobil had together devoted more cash to capital expenditures than shareholder returns for at least 28 straight quarters, according to FactSet. The ratio has been the opposite every quarter since, with the companies paying out $14.8 billion in dividends and buybacks in the first three months of this year, compared with $8.4 billion in capital investment.

Mr. Breber said the San Ramon, Calif.-based Chevron, which boasts almost $15.7 billion in cash and cash equivalents, could operate with a balance sheet one-third the size.

"We want to return it [to shareholders] through the cycle in a steady way," he told analysts.

Other U.S. companies have more recently followed the majors' lead. At ConocoPhillips and 48 smaller publicly traded oil-and-gas firms, executives in the fourth quarter of 2022 funneled 42% of the cash they used into shareholder returns, according to an analysis of financial disclosures by Evaluate Energy. Capital investments comprised 35% of such funds in that period -- down from 67% in the first quarter of 2020.

"U.S. oil-and-gas producers are less focused on capital spending than they have been in years," said Mark Young, a senior analyst at Evaluate Energy.

The cash buildup owes itself to other factors as well. Many companies have paid off debt racked up during growth mode, when they dug much of the top-tier territory for wells. While some companies have pledged huge sums to carbon-capture technology or hydrogen production, clean-energy investment has been slowed by lower expected returns and the wait for yet-to-be-finalized regulations in Mr. Biden's climate package.

Large companies such as Exxon Mobil have also explored acquisitions to scoop up independent or privately held drillers with faster-growing shale output, The Wall Street Journal has reported.

Exxon dwarfed other U.S. companies in the first quarter with nearly $32.7 billion cash on hand, up about $3 billion from the end of last year. With yields on short-term investments such as Treasurys higher than what Exxon pays on its debt, "we're not incurring a negative cost of carry on that cash balance," Chief Financial Officer Kathryn Mikells told analysts on an earnings call.

That financial reality, brought on in part by Federal Reserve interest-rate increases aimed at slowing the economy, is changing the idea of what makes an optimal balance sheet for oil companies in an unpredictable market, said Sam Margolin, an analyst at Wolfe Research.

"It definitely takes the pressure off of trying to jettison cash as quickly as possible," he said.

Comments