The $10 Trillion Hidden Debt Problem!

One of my top 10 read pieces is “Canary In The Coal Mine”, which I wrote last year, demystifying the “troublesome” Chinese property sector.

Some people would argue that Chinese Real Estate (RE) forms a small share of the total RE wealth globally; however, one can’t ignore the gargantuan building spree that China has undertaken in the last two decades. China was solely responsible for the commodity bull market that ensued in the first decade of the 21st century.

Nevertheless, as the Chinese RE sector peaked and indicated the first signs of a slowdown beginning in 2016–17, the commodities since then have traded sideways (except the post covid bull run, which has now fizzled out).

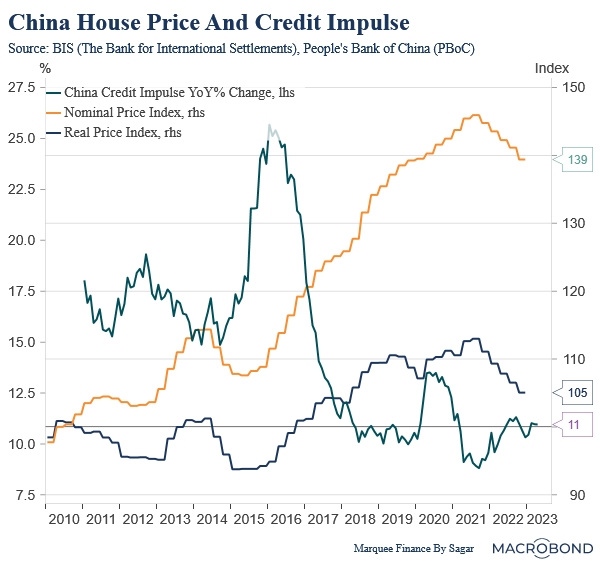

The tremendous rise in Chinese Credit Impulse in 2015 gave massive impetus to property prices. Nonetheless, it looks that that was the final leg of the rally before the meltdown occurred as a string of defaults plagued the nation’s lifeline led by the infamous “Evergrande” episode.

One thing is certain: “The commodities bull market can’t sustain without Chinese property market revival”.

Folks, we must appreciate that the twin-engine of China’s breakneck growth was the building boom in the “property sector” and the unprecedented “infrastructure” spending.

However, when one digs deeper into the cobweb of infrastructure financing, one is astonished to witness the “Canary in the Coal Mine-2”, which will drag down not only China’s long-term growth but also will be massively deflationary akin to the Japanese 80s property bubble bust.

Let’s Go!!

Financing The Infrastructure Bubble!

An SPV: “Special Purpose Vehicle” is a legal entity that isolates the parent firm from financial risk. As the name mentions, it’s designed to fulfil “certain” specific objectives and is considered “bankruptcy-remote”.

In China, the local governments financed gigantic trillions of dollars of infrastructure projects in the last two-three decades using SPVs known as “Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs)”.

LGFVs are set up by local authorities to borrow money for funding infrastructure and public welfare spending.

The salient feature one needs to remember about LGFVs is that the LGFV bonds are “usually” not allowed to be repaid from government fiscal revenue.

This is a significant concern because if the project becomes/is unviable due to force majeure circumstances or exogenous factors, the LGFVs will default, and the bondholders will suffer losses.

Nevertheless, before we go to the nitty gritty of these SPVs, we need to understand a bit of history.

PART 1: 2008–2015

It all started with the breathtaking stimulus of 3 trillion Yuan that the Chinese Government launched post the 2008 GFC. This stimulus encouraged the local governments to borrow money via LGFVs and spend on public infrastructure projects.

As a result, by the end of 2009, LGFVs had already accumulated 5 trillion yuan in bank loans. In 2009 (a single year), the debt ballooned by 3 trillion Yuan!

By mid-2013, total indebtedness at LGFVs reached 6.97 trillion yuan, almost 40% of the total 17.9 trillion yuan borrowings.

But why LFGVs?

The local governments in China until 2014 had limited options to raise money except for the local taxes (that too the control is with the central government).

Direct borrowing was prohibited, and as a result, the local governments used LGFVs to borrow and lavishly spend for their notable infrastructure spends.

This was an innovative way to gear up leverage in the form of “off-balance sheet items”, which kept the true health of the state governments concealed from the public eye.

But something changed in 2013–14:

As the LGFV’s borrowings saw a colossal rise, an audit was conducted in 2011 audit. The result was legal amendments that prohibited local governments from borrowing via LGFVs and a plan to refinance NAO-identified public liabilities into sub-sovereign bonds issued directly by provincial governments.

Despite shifting some 14 trillion RMB in LGFV debt to the official public balance sheet as part of a debt-swap program, LGFV borrowing continued to grow, prompting renewed efforts to limit the use of LGFV borrowing.

PART 2: 2015–2020

In 2015, the ban was raised, and the local governments were permitted to raise money via bonds and bank borrowings.

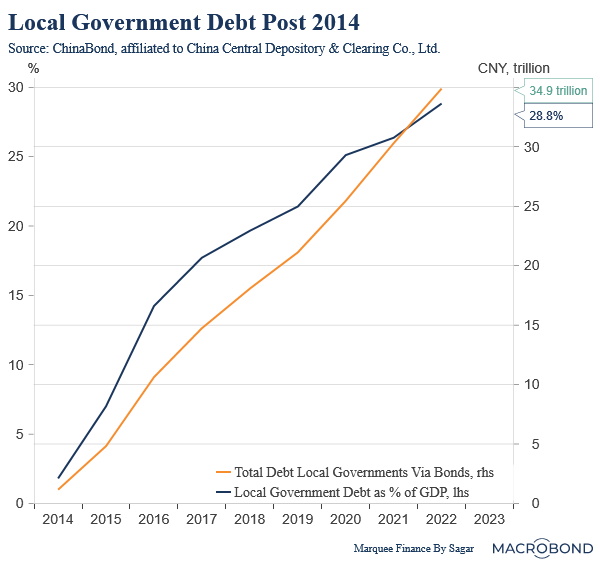

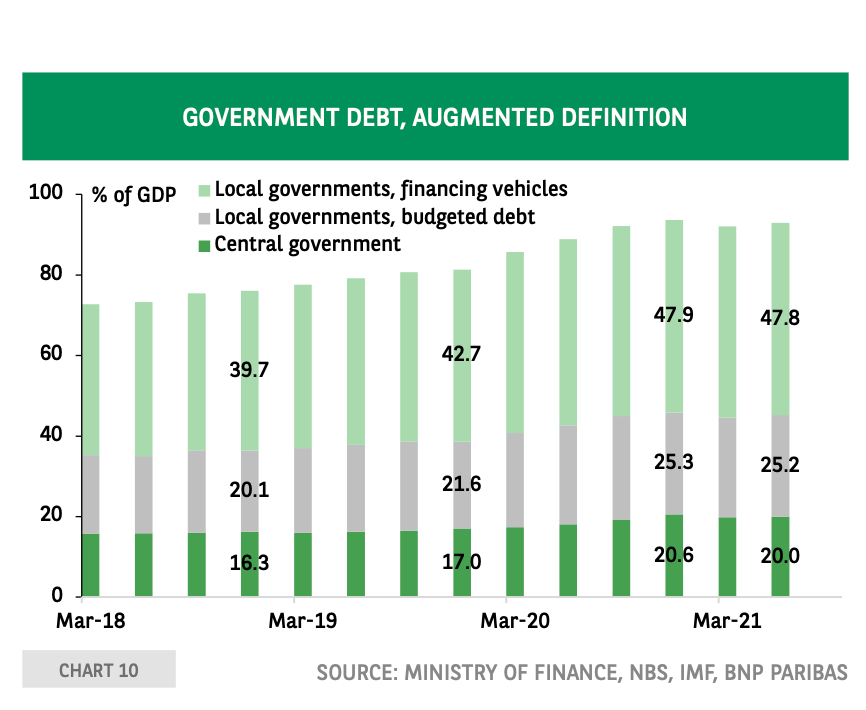

And the local government’s borrowings saw a colossal increase. The borrowings reached a mind-blowing 28% of GDP within a few years!

Though some of the increase can be attributed to the LGFV debt swap mentioned earlier.

Furthermore, the massive increase post-2016 explains the rise in the credit impulse, which I mentioned in the beginning.

Nevertheless, the local governments also continued to raise money via LGFVs in another ingenious way.

The fastest growing portion of the LGFVs balance sheet was the “receivables” component. These were the arrears of local governments towards these opaque SPVs.

You will be stunned to know that the receivables from local governments were equivalent to 18% of GDP in 2020, as per the IMF.

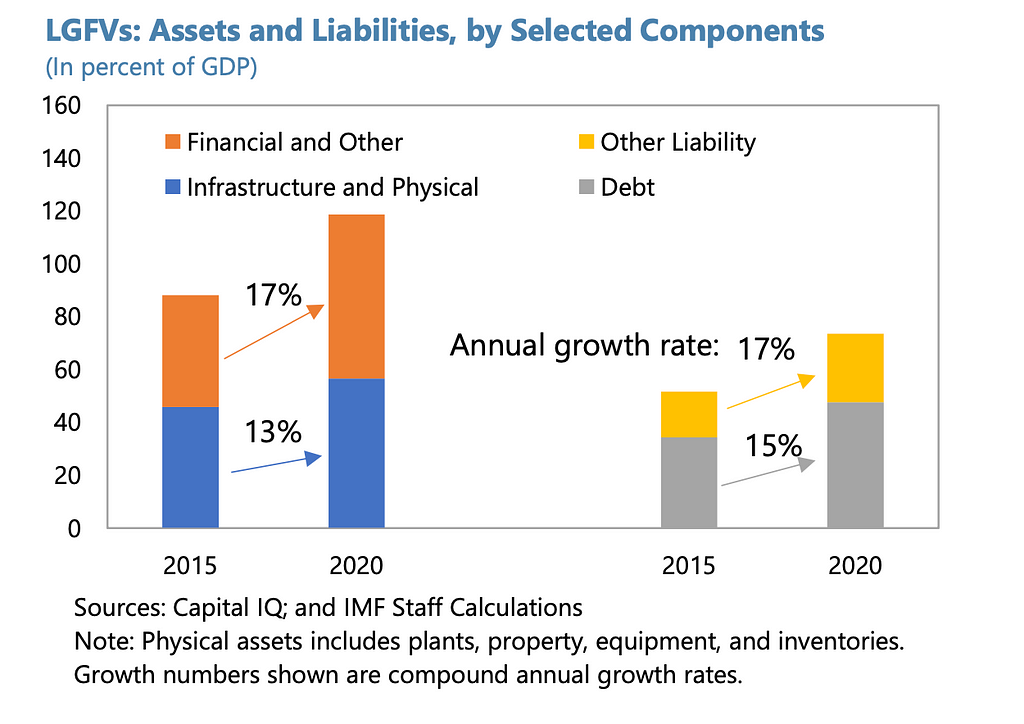

On the liabilities side, we can see from the chart that the debt grew at an astonishing 15% CAGR. On the asset side, the growth driver was primarily financial assets comprising accounts receivable and investments in securities, cash, loans, company equity and other unspecified tangible assets.

One can ascertain the constant need for increasing debt/leverage by digging deeper.

The precarious position of LFGVs is clear, as more than 85% of the source of funds is external financing, which is clearly shocking.

“This means that these entities are deep in the red (negative operating cash flow) and needs to borrow massively every year just to meet their operating expenses.”

In fact, LGFVs accounted for a large part of the total social financing for non-financial firms.

Are LGFVs Insolvent?

The million-dollar question for many Chinese investors is what happens with the LGFVs, or in other words, do these SPVs pose a systematic risk to the Chinese financial system?

Let us look at some of the figures to know the extent of damage that these LGFVs pose:

Alarming Concern:

- The stock of LGFV debt-at-risk, defined as debt not backed by earnings sufficient to cover interest payments, is equivalent to about 37% of GDP. Thus, the majority of LGFVs are “zombies” in nature. These are the primary contributor to China’s elevated debt vulnerabilities.

- The prominent concern regarding LGFVs is their meagre Returns on Assets (RoA-mainly infrastructure). These have very long payback periods and rely on uncertain cash flows. Therefore, the debt on these assets requires continuous restructuring.

- External financing of operating costs like payrolls and land purchases generates new interest-bearing debt for LGFVs. This potentially results in collateral damage as a lack of cash flows to cover interest costs compounds entity-level LGFV debt.

- LGFVs account for 14.7 % of outstanding bank loans. You will be astounded to hear that even a tiny % LGFV default rate of 5% would result in a roughly 75% increase in Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) of Chinese banks.

- Furthermore, most of the local government bonds (up to 80%) are owned by regional commercial banks, which is a precursor of elevated concentration risk; and can lead to potential systematic risk.

- Ultimately, it’s expected that the LGFVs will lead to an exponential increase in potential contingent sovereign liabilities.

As per market reports, debt amounting to about 20.1 trillion RMB as of 2020, or 44% of total LGFV debt, is unsustainable due to the abovementioned features.

The draconian two-year-long Chinese Zero-Covid policy magnified the problems for LGFVs and, thus, the local governments as the cash flows dried up for most of the infrastructure projects.

Lately, the investors have been taking note, and the premiums have been rising for the LGFV bonds over the sovereign paper.

The Road Ahead!

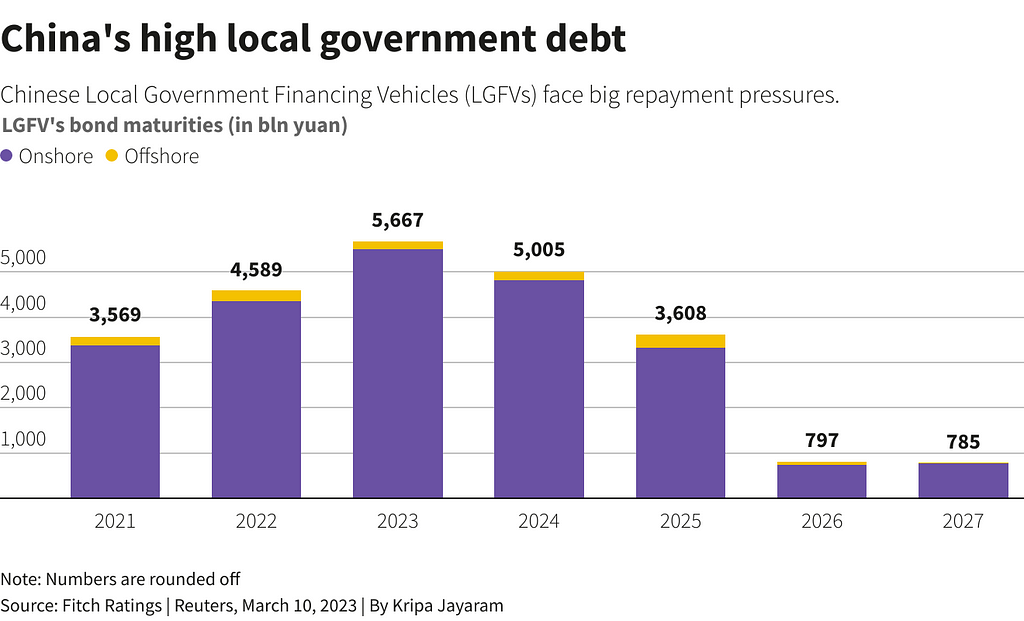

As the maturities approach, there will be a system-wide potential restructuring across the LGFVs. We have already seen that some of the “weaker” local governments have pursued restructuring in the last few months.

As per Reuters: “Govt financing vehicle in China’s Guizhou region extends debt by 20 years.”

As per BBG: “Yunnan province, of which Kunming is the capital, took a heavy hit last year from slowing economic growth and China’s property market slump. General budget revenue in Kunming that includes taxes slid 27% while government-fund revenue, which is mainly income from land sales, plunged 68%.”

The result of these restructurings will be the deteriorating creditworthiness of the local governments that control them.

Furthermore, debt maturities will spike drastically in the next few years.

As the wave of restructuring hits, the repercussions will be massive:

- The regional banks might need to raise fresh capital or else face demise.

- The Local government’s borrowing cost might increase going forward,straining their finances further.

The ultimate nail in the coffin will be the central government intervening and giving the implicit guarantee to prevent contagion from spreading in the Chinese financial system.

These might lead to the weakening of the Yuan and can also lead to credit agencies downgrading sovereign debt.

Conclusion!

Even without new infrastructure financing, the local government’s debt continues to skyrocket due to “insolvent” LGFVs (Negative Cash Flows) and plunging tax revenues as the property sector meltdown transpires.

According to IMF estimates, the total debt of LGFVs and other extra-budgetary funds handling public investment on behalf of Local Governments has increased by 15–20% CAGR since 2018.

The Chinese Government will have to find a possible solution and restructure the debt (which will undoubtedly be painful) so that the defaults do not pose a systematic risk to the Chinese banking system.

Canary In The Coal Mine- 2! was originally published in DataDrivenInvestor on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Comments