I published a new options post today. It’s one I’ve been meaning to put out for a while and it’s been sucking up most of my recent writing time. At the end of this post, I’ll explain what unlocked it for me.

A walk-thru of the new post:

Short Where She Lands, Long Where She Ain’t (Moontower)

🪝 The hook

“The most you can lose when you buy an option is the premium”

True or False?

- The Series 7 answer is True

- The volatility trader who delta hedges will say False

Moontower says…let’s see how much mileage we can get from such a simple question. How will we measure success?

Nothing less than completely changing how you think of options.

Intro

Newcomers to options see

buying them as:

- a source of leverage

- a “cheap” way to express directional views

selling them as:

- coupons to be clipped. If they go in-the-money they rationalize “I’ll be happy if it gets there” because it’s a cash-secured put or a covered call.

In both cases, these investors are fixated on “hockey stick diagrams”.

The diagrams are important in the same way that knowing the location of a race is important — you have to start somewhere. The diagrams represent the payoff of a long or short put/call at expiration. And to be clear, where the stock rests when expiration arrives is important, but the diagrams are a woefully incomplete story in the context of how options are used in practice.

[I’d argue that the most important insight from the diagrams is a visual proof of put-call parity — and the core insight of p/c parity is options have nothing to do with direction since calls and puts are substitutes for each other.]

My one-line description of this post:

What vol traders understand that regular option users don’t…and why they should

Clues About The Nature of Options

For an options novice, the following statements about risk are familiar and uncontroversial:

- If you buy an option, the most you can lose is the premium

- If you sell a call, your potential loss is unlimited

- If you sell a put, you can lose as much as the strike price (ie the case where the stock goes to zero)

If you delta hedge an option, the situation changes:

When you buy an option, you can lose way more than the premium

At this point, the post goes through some numerical examples and establishes key observations. These bring the reader to a realization that vol traders all understand:

Option trading is about being short the options where she lands and long where she ain’t.

It’s an expression I’ve tossed on Twitter a few times over the years. Lemon replied:

It’s an insight that didn’t crystallize for me until maybe 5 years into option trading. Of course, I understood that if a stock expires on my long long strike or blows throws my short strike I’ll get crushed. But it’s one thing to observe this dynamic, and another to internalize it to guide how you want to express trades.

By working through the post, you will start to see options in a new light. For many, it will quite literally flip how they think they should use them. As a treat, the process for building this understanding is filled with all kinds of minor insights along the way that fill grout in your trading literacy.

Simulations

This is the heavy-lifting part of the post. But it’s also skippable:

While there are useful insights from understanding the simulations, you can still get plenty of value from skipping ahead to the Discussion if you prefer.

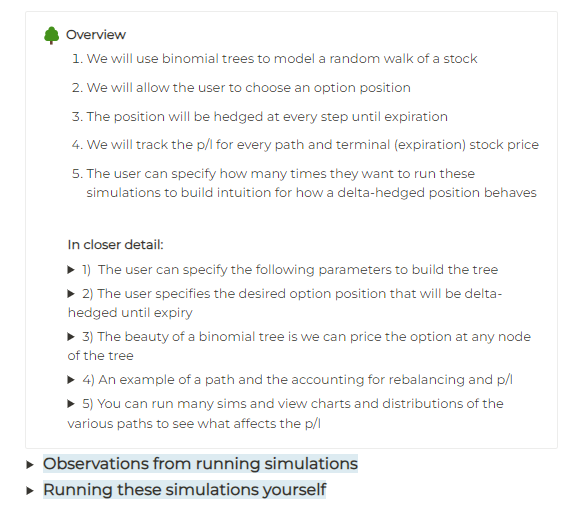

This is what it looks like and yes you can drill down into all of it. There’s plenty to check out without running sims yourself but if you want the full monty, the python code is on Github. The “Running these simulations yourself” section is a companion that should make that process painless.

If you prefer to just skip over levels like Mario hopping into a green pipe, just go to the last section:

Discussion

You’ll find 3 high-level insights followed by 4 questions:

- If you are not a delta-hedger, but trading the options outright for direction does this matter?

- You are a market-maker and see a giant flurry of call buying in the context of bullish news. You decide the buyers are overpaying — the prices are implying a volatility your process has deemed as “excessive”.

Do you hope the call buyers are right? - How can I use this knowledge to shape trade expressions?

- I have a hunch my boss doesn’t really understand options but he trades them a lot. Is there a way to tell?

The post has the answers. Here’s the link again:

https://notion.moontowermeta.com/short-where-she-lands-long-where-she-aint

So why did it take so long to get around to a post I thought was important?

I knew I wanted a way to demonstrate the principle via simulation not just words. Coding is a slog for me so there was enough friction to just keep punting this. But GPT-4 changed the game. It was my assistant the entire way. Every single line of the graphing code was written by GPT. All the debugging was done by GPT. I’d give it all the code and the error and it would just give me the exact code to fix it. I’m almost shaken by how helpful it was.

The experience has given me some new ideas for things I can actually prototype that I didn’t think was possible to do on my own (I’ll of course share them when they exist).

Agustin Lebron tweeted this last week:

The LLM as a put option on cognitive tasks. Almost a year into the world’s experience with ChatGPT, it’s pretty clear that its biggest value is helping people with things they’re not good at.

It’s not going to write the next great American novel, but it will write that annoying blog post you need to churn out. — If you’re not great at data analysis, Code Interpreter will do a fine job. — It won’t make you an edge-level researcher, but it can help you learn faster.

It will write decent code for problems that have been solved a bunch of times before (React frontend, Flask backend, etc) but won’t design the perfect task-specific data structure or type hierarchy for a new problem. Basically, it makes you decent at what you’re not good at.

That’s basically the definition of a put option. It gives you a cap on the amount you’re going to lose relative to a competitive world in situations where you’re not that good. Using an LLM is like cheaply buying puts on the holes in your cognitive skillset.

So how should you rationally adjust your behavior given you own these cheap puts? Embrace variance! Your value to the world less dependent on what you’re worst at, but more dependent on what you’re good at.

So go out and hyperfocus! Whatever it is that interests you so much you focus on it to the exclusion of all else, go do it and feel no guilt. LLMs got your back.

I replied in agreement:

If you subscribe to “lean into your strengths and just spend the minimum to get your weaknesses serviceable” the LLMs just raised the strike for the same given cost.

I’ll round this out with one more idea that spares you the option analogies:

The Brilliant Math Coach Teaching America’s Kids to Outsmart AI (WSJ)

If you have anxiety about the overwhelming technological pace change this post can help reconcile your thinking about these tools and how to use them to complement what humans are best at.

Po-Shen Loh, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University and Team USA’s coach for the International Mathematical Olympiad, is traveling to 65 cities and giving 124 lectures before the next school year like he’s on a personal mission to meet every single American math geek.

His simple advice for an uncertain future: Be more human.

Check out the post to see what he means.

I wouldn’t sit on your generative urges. It’s never been easier to take em off-leash.

Comments