Beijing is shifting its governance priorities to balancing growth and sustainability, tackling social equality and security with a major regulatory reset. It could rebalance the share of economy toward labor, lowering corporate profit share. We see a longer and more profound market impact.

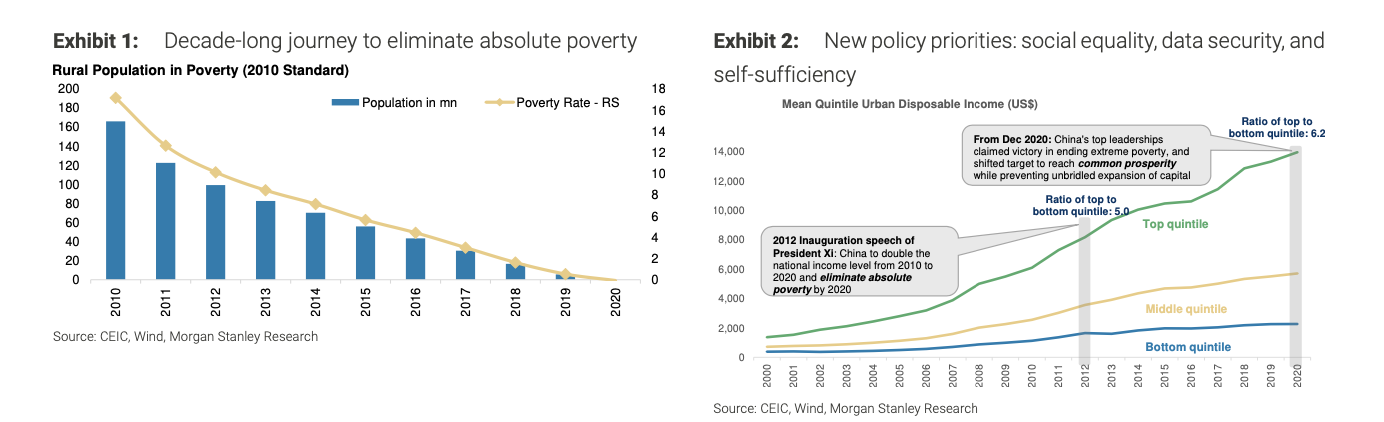

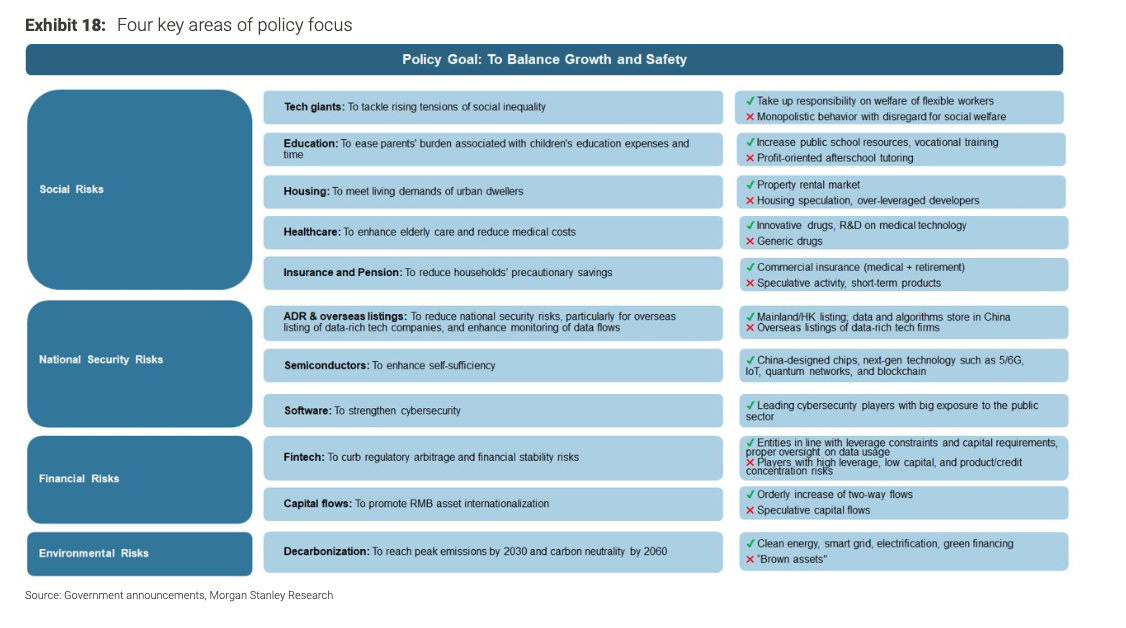

New objective triggering major regulatory reset: We are at a signifi- cant moment in the history of China’s economy and capital markets: after a decade-long journey to eliminate absolute poverty, Beijing is shifting governance priorities from growth to balancing growth and sustainability: social equality, data security, and self-sufficiency. China's new regulations on fintech, big tech, after-school tutoring, cryptocurrency, and carbon emissions over the past nine months underpin this major regulatory reset.

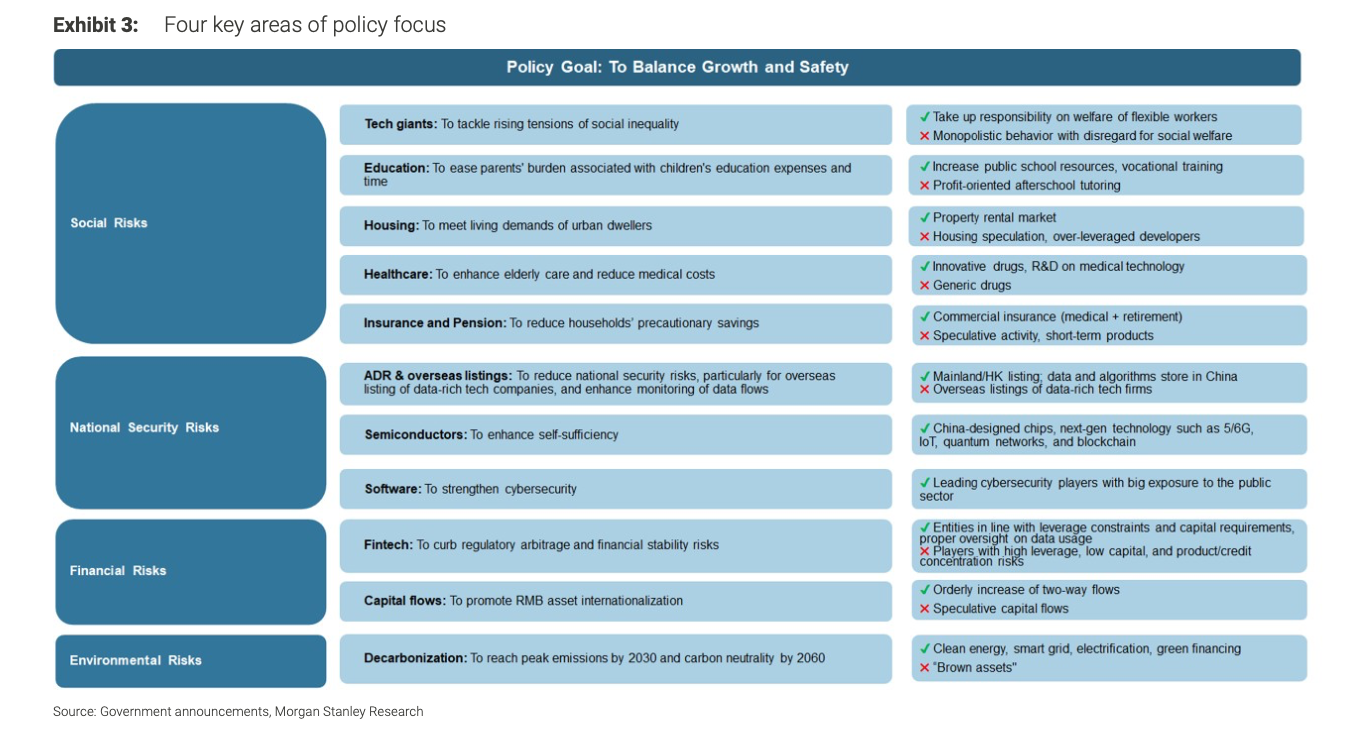

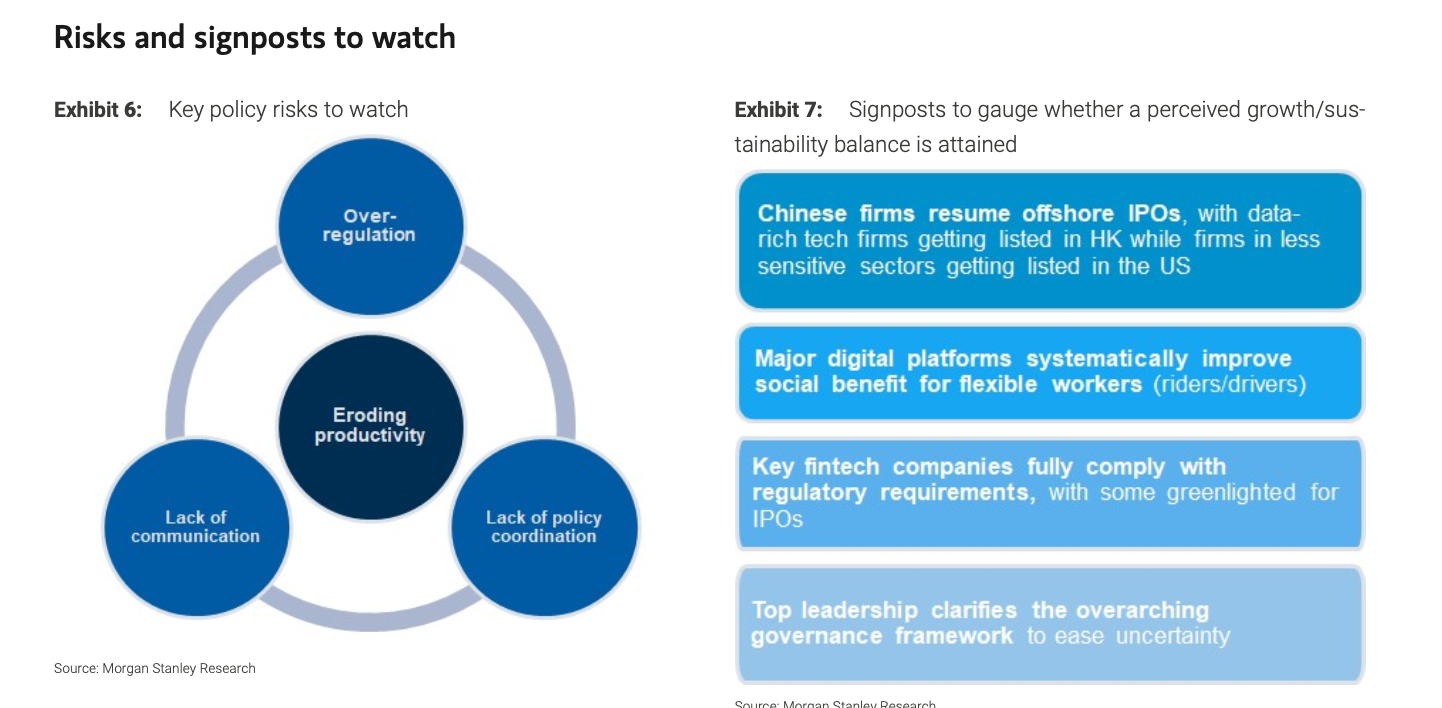

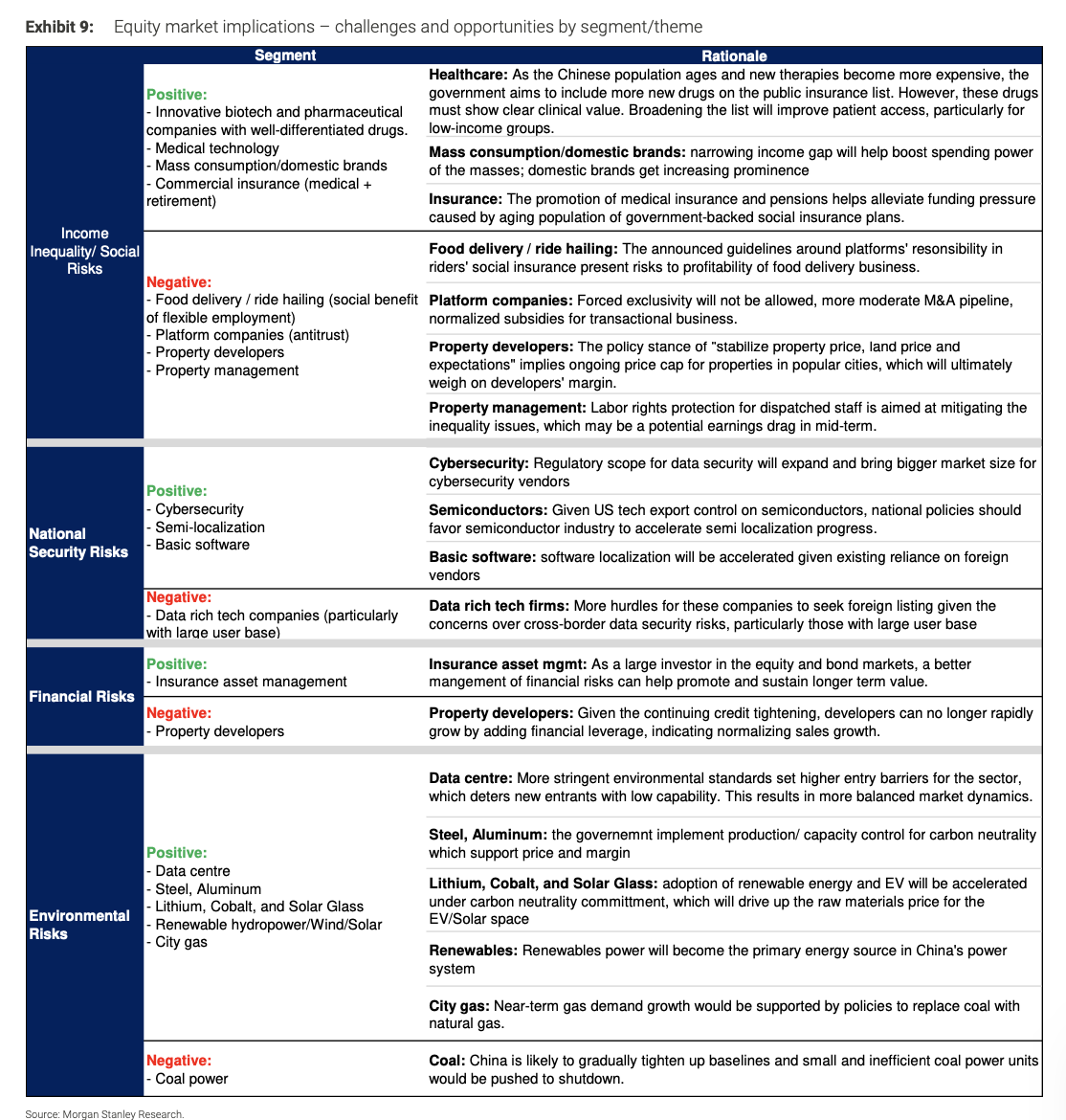

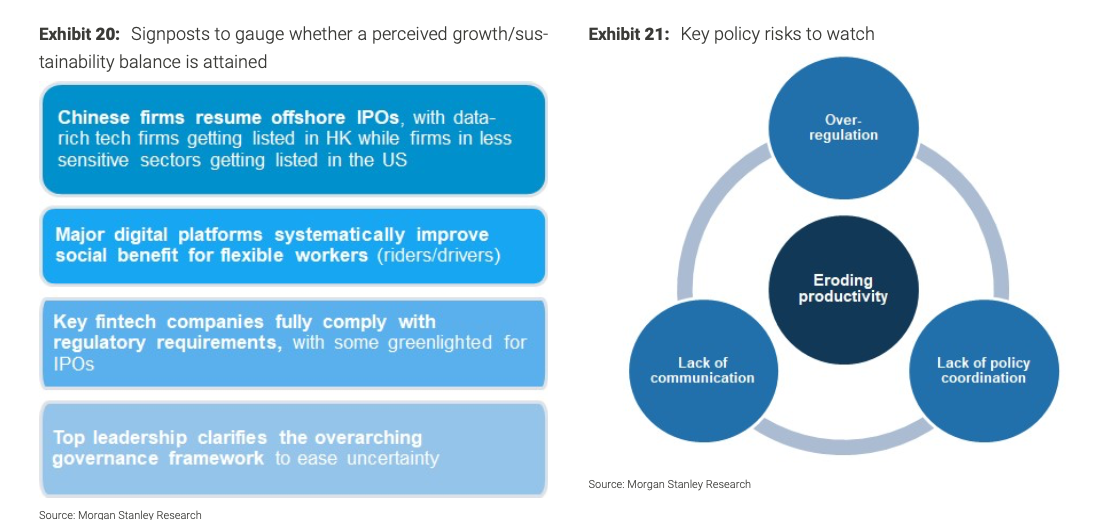

Economic implications: Under the new governance paradigm, China appears to be attempting to check the rise in corporate power and rebalance the share of the economy in favor of labor, which could result in decline in corporate profit share. We see regulatory head- winds for sectors associated with rising tensions of social inequality, environmental sustainability, and data security risks, while the new framework provides policy support to advanced manufacturing, tech localization, and renewable energy. We remain watchful of the risk of over-regulation, or, in contrast, resumption of offshore (Hong Kong) IPOs for tech companies, clarity over employment benefits and other issues concerning platform companies, progress on audit access dis- pute resolution, and clearer guidance from top policymakers to curb spillover effects of regulation changes.

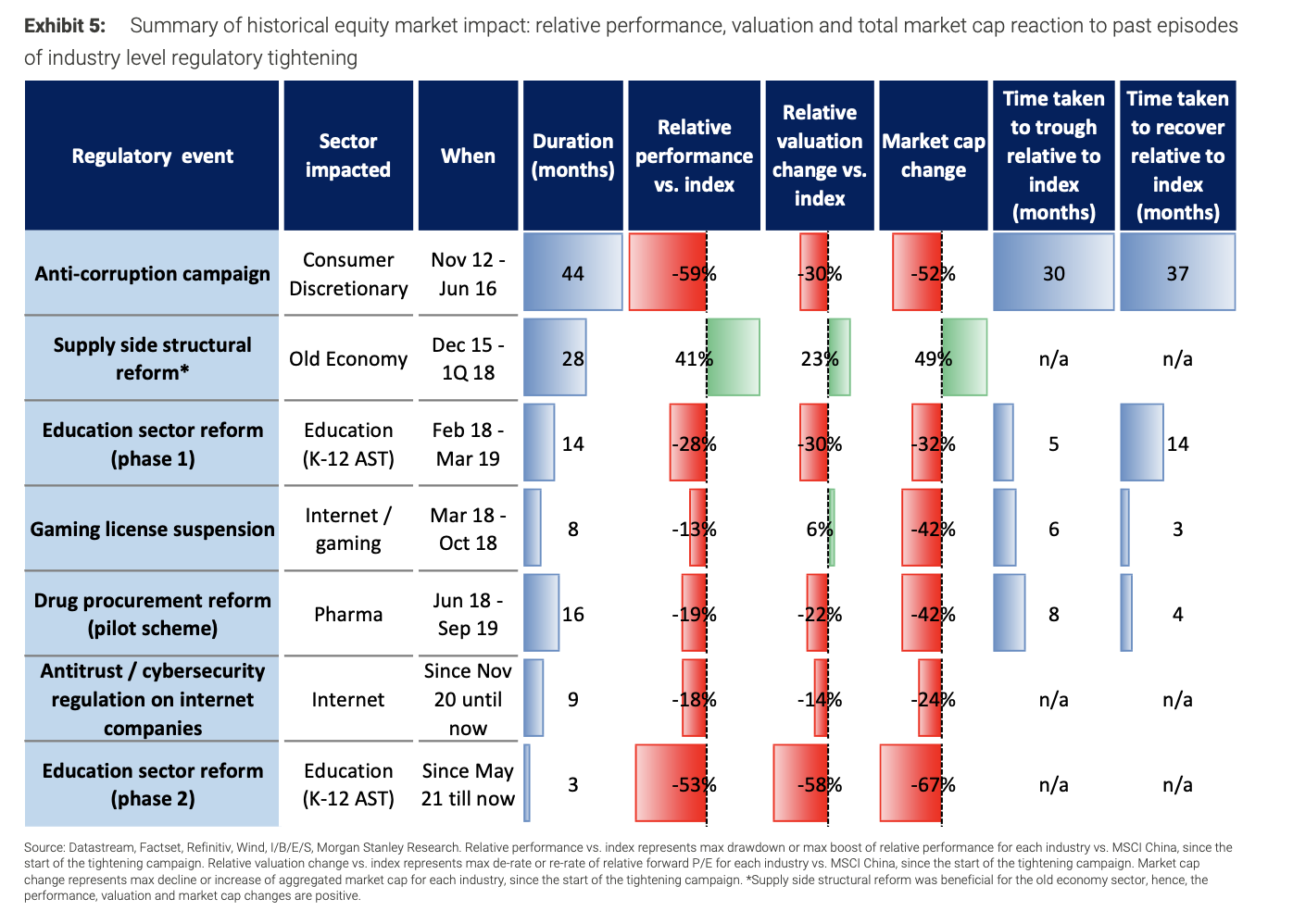

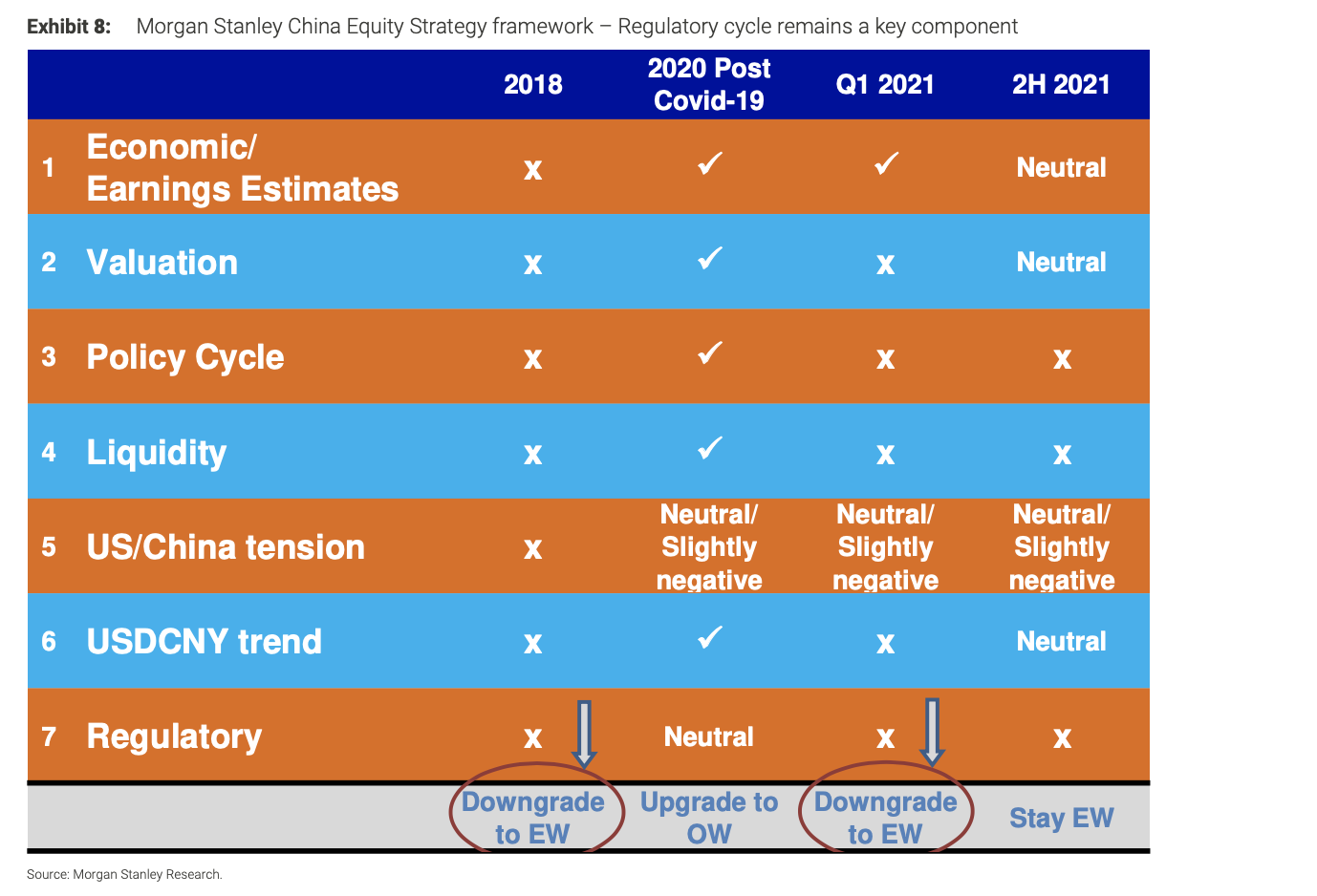

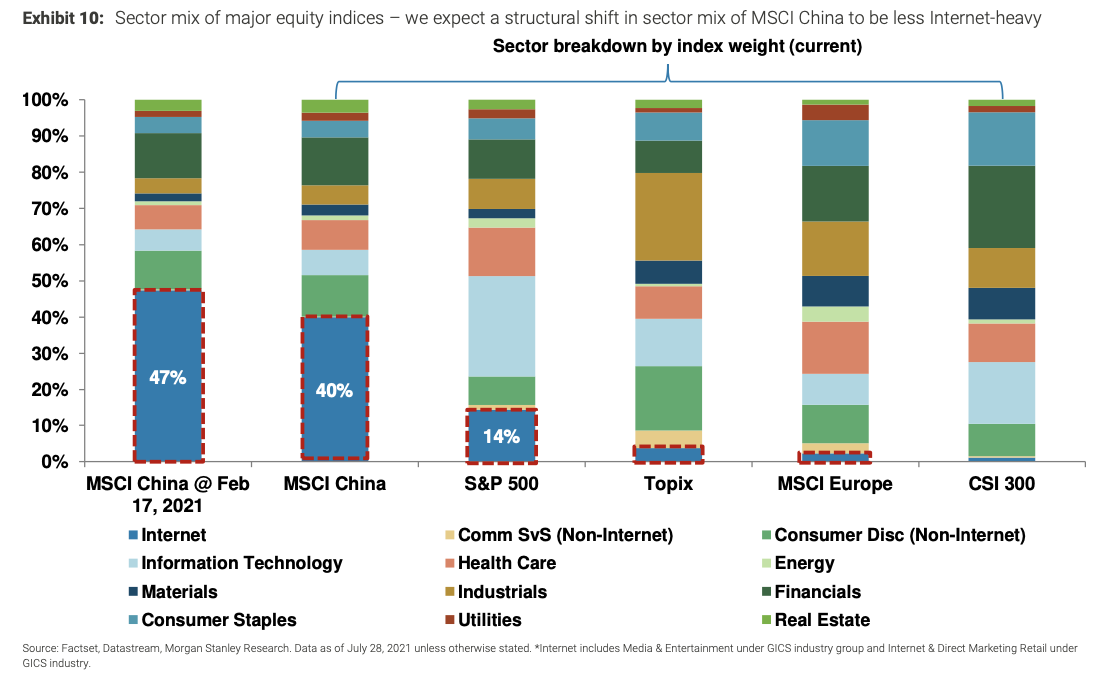

Investment implications: We expect a longer and more profound impact from the current regulatory cycle on China's equity market valuations and Equity Risk Premium (ERP) than has occurred in sim- ilar past cycles, as it is affecting a more substantial proportion of the market than previously and, in particular, the Internet sector, which accounts for ~40% of MSCI China by index weight. There is a substan- tial degree of uncertainty over what this means both for future net income margins and revenue growth for the affected sectors and stocks.

Our current base case forward P/E target for MSCI China of 13.0x implies MSCI China would trade on a mid-single-digit percentage val- uation discount to MSCI EM ex China for a sustained period of time. Over time we expect the MSCI China universe to gradually have a more balanced sector allocation with a reduced weight for Internet and a higher weight for sectors like Industrials and IT.

Challenges and opportunities by segment/theme: Data-heavy tech and platform companies and property could remain under pressure amid the regulatory reset, while semi localization, cybersecurity, domestic brands catering to the mass market, innovative drugs, bio- tech, and green economy may enjoy support.

5 Key Charts at a Glance

A shift from "growth first" to balancing growth and sustainability...

New era, new objective...

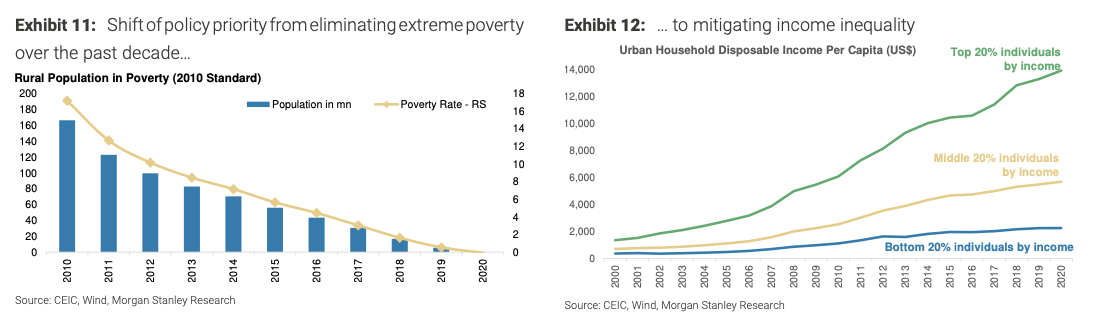

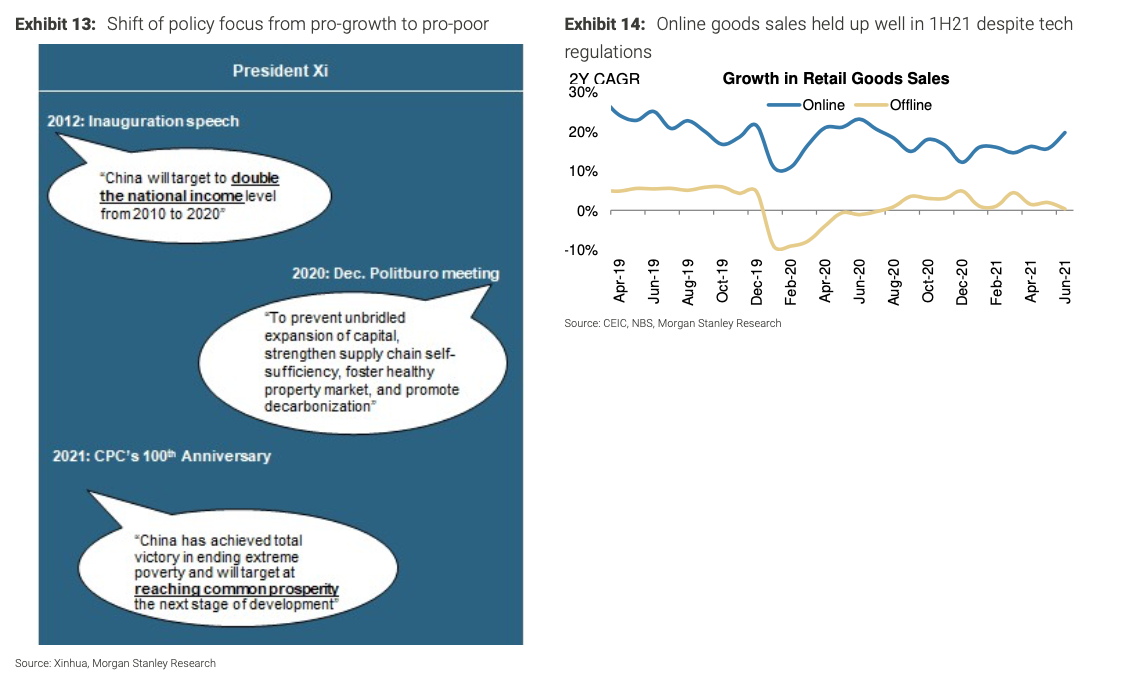

We believe the recent regulatory tightening reflects a shift in China's governance priorities from "growth first" to balancing growth and sustainability – i.e., security, self-sufficiency, and social equality. In the last decade Beijing said its key goal was to double per capita income and eliminate absolute poverty (President Xi’s inaugural speech in Nov. 2012), i.e., giving highest priority to growth. However, this "pro-growth" strategy also led to higher inequality and social problems due to lack of regulations on emerging sectors, pointing to the importance of "pro-poor" measures as a complement (see World Bank (2004): Pro-growth, pro-poor: Is there a tradeoff?). Now, the government is emphasizing “getting rich together” (common prosperity) as the new objective for the next stage of development in the midst of the CCP's 100-year anniversary, and aims to "prevent the unbridled expansion of capital" by intro- ducing a range of KPIs besides economic growth, which covers social equality, supply chain self-sufficiency and data security in the face of rising secular risks – income inequality, US-China tensions, and aging demographics.

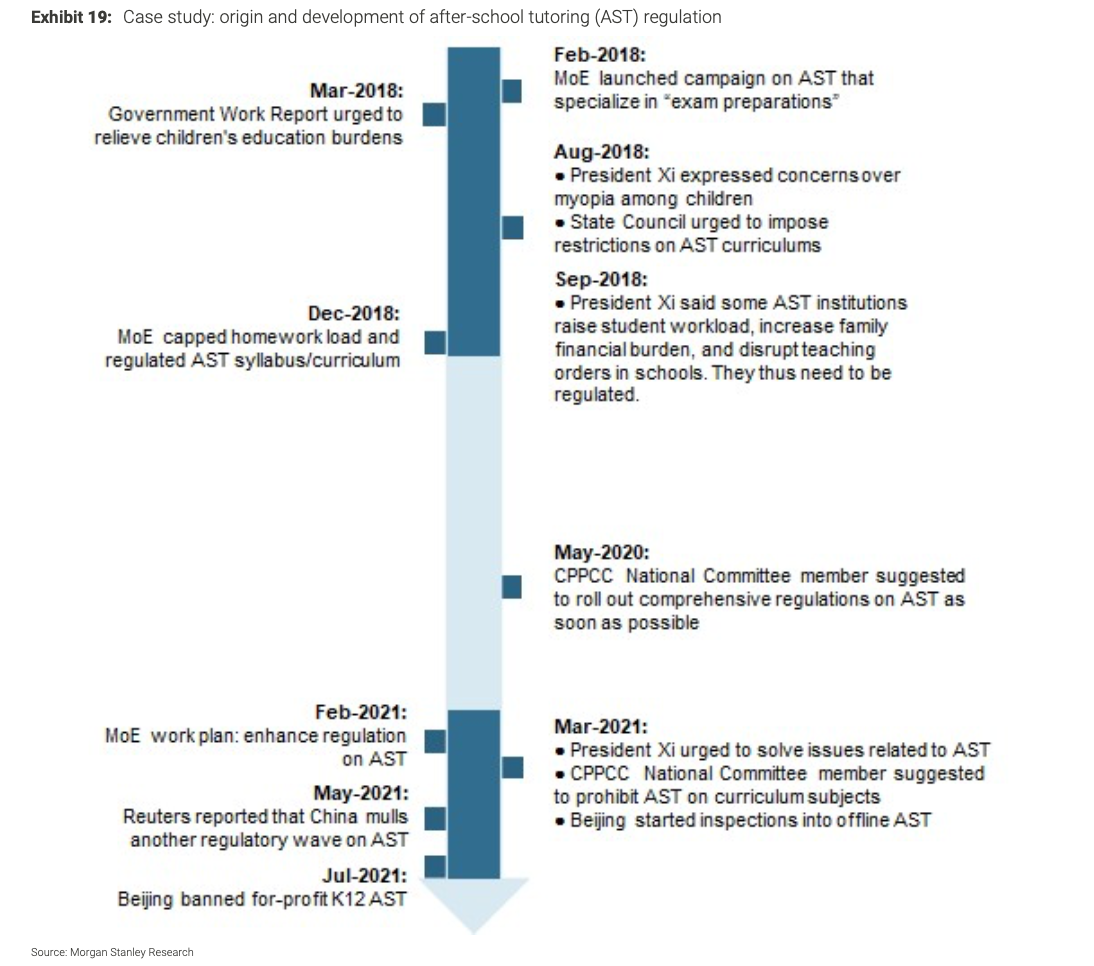

Reflecting this reorientation, policymakers have intensified regu- lations in the past 9 months over fintech, big tech (anti-trust, data regulation and employee protection), after-school tutoring, crypto- currency, carbon emissions and overseas IPO rules. The anti-trust campaign has mainly targeted the prevention of tech giants from an over-concentration of market power and eroding welfare of smaller businesses and outsourced employees; the fintech regulation serves the purpose of curbing regulatory arbitrage and financial stability risks; and the increased scrutiny over Chinese ADRs and cross-border data flow in July 2021 mainly focuses on reducing risks of security amid lingering geopolitical tensions. Similarly, the recent regulatory changes to after-school tutoring are part of policy efforts to reduce child-raising costs.

In short, China is trying to rebalance the rise in corporate power and the share of labor compensation, and this may lead to some systematic de-rating in valuations for some sectors. Having said that, policymakers will have to strike a balance, as China's ambition to thrive as an economic super power will require it to ensure con- tinued private sector vitality to spur innovation and further RMB internationalization to attract capital inflows, so as to sustain long- term productivity growth. While the new regulations introduce more requirements on social responsibility and data usage, and might lead to some increase in margin pressures for related enterprises, we think they will not disrupt business models for most sectors (except for after-school tutoring). For instance, the anti-trust law mainly focuses on banning tech-giants from requiring merchants to sign exclusive cooperation pacts, while the government's guidance on enhancing flexible workers' social benefits mainly requires food delivery platforms to pay healthcare and pension coverage for out- sourced employees. Online goods sales have also held up quite well recently despite the tech regulation campaign starting from late last year. Meanwhile, some regulatory changes are supportive for advanced manufacturing, hardware localization, and clean energy supply chain.

While many of the regulations appear long-overdue and make sense (for example on fintech, anti-trust and outsourced labour protec- tion), the pace of changes in last 9 months has caught the market off-guard as a seemingly arbitrary shift in direction.

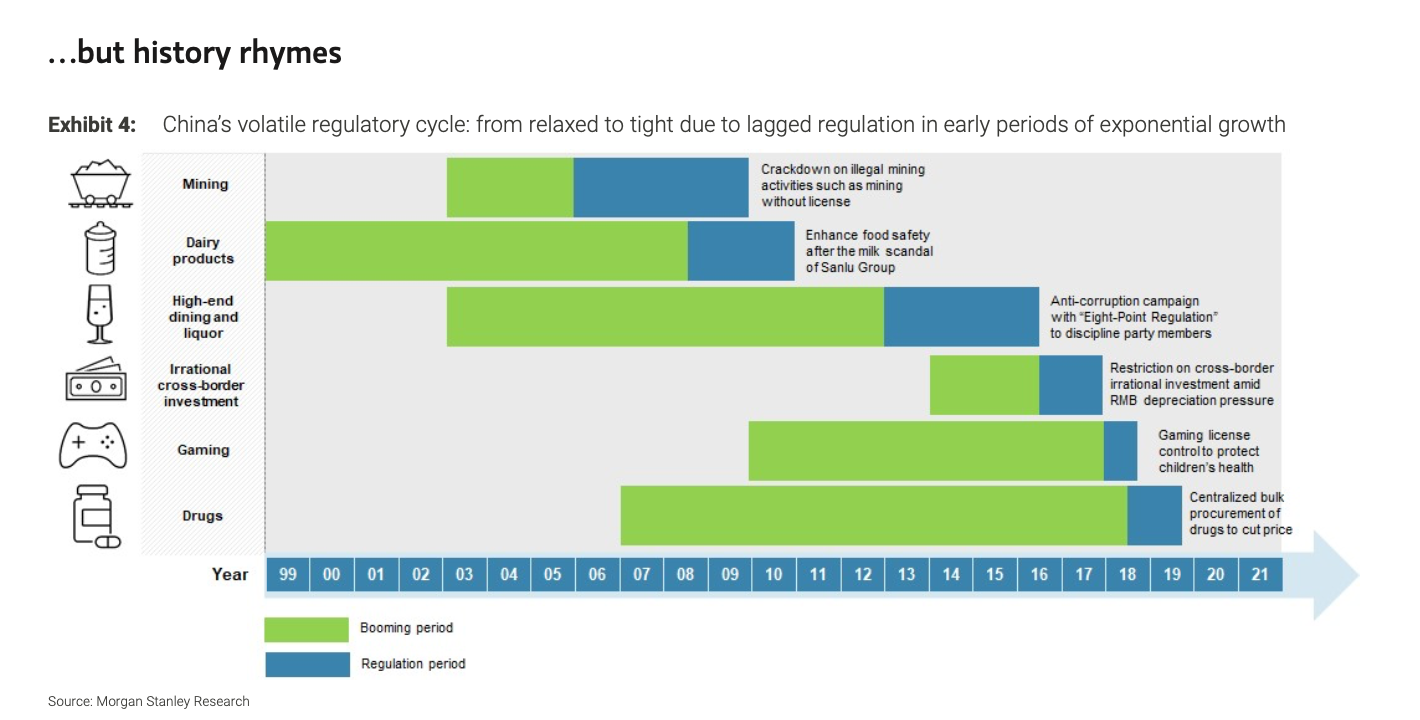

Why has it occurred in such fashion? We have indeed seen this movie many times: China’s regulatory environments have tended to oscillate between relaxed and tight enforcement, especially in emerging sectors. But this has tended to result in an abrupt regula- tory reset. Before the current reversal in regulating big tech, China had a regulation campaign on mining (2006-2009), dairy (2008- 2010), high-end dining and liquor (2013-2014), irrational capital out- flows (2016-17), gaming (2018), and drugs (2018-2019) – most lasting for one to two years. The sharp shifts in regulatory changes have been largely due to the fact that regulations have tended to lag a period of exponential growth in the sector:

- Relaxed stage: Local government support, pro-growth men- tality and business interests together contributed to a lag in regulating emerging sectors.

- Tight regulation stage: When a problem is looming as evi- denced by public opinion and/or financial stability indicators, the top leadership shifts gears, quickly mobilizes all administra- tive resources to reorientate its policy control and bolster its regulatory capacity.

However, the abrupt shifts in policy tend to hurt market confi- dence and would benefit from more clarity: In past regulatory cycles, capital markets usually underperformed at the start, reflecting weaker market sentiment in the face of policy uncertainty, suggesting the need for greater policy communication. Historical patterns suggest that as an initial step to restore private sector confi- dence, minister-level officials attempt to clarify policy goals publicly. But if this communication is insufficient to temper concern and even- tually weakness in private confidence hurts the job market, top-level policymakers tend to step in.

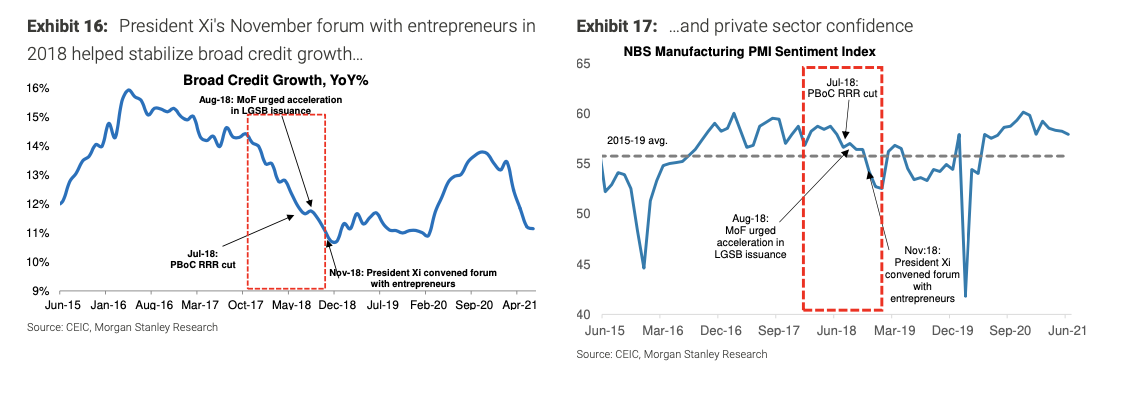

Here we can take 2H18 as an example, when the triple headwinds of deleveraging, regulatory tightening, and US-China trade tensions triggered market concerns about "state advances, private sector retreats". By then, while policymakers already shifted to an easing stance in July 2018 with PBoC's targeted RRR cut, followed by the Ministry of Finance's urge to accelerate local govt. bond issuance in August 2018, it did not stop the deterioration in broad credit growth and private sector confidence. In response, China's President con- vened a forum with entrepreneurs in November 2018 to send a clear signal on supporting private firms.

We also see a similar pattern emerging from the government in trying to provide clarity in this cycle. For instance, China's Vice Premier spoke at a business forum on July 27, saying that the nation would "strike a balance between growth and safety, to ensure social fairness and competition, and promote healthy development of the capital market". According to Bloomberg, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) also told major investment banks on July 28 that the education policies were targeted and not intended to hurt com- panies in other industries. Separately, the government of Zhejiang province (one of China's richest provinces) clarified in mid-July that the “common prosperity initiative” does not mean "absolute equal". We will be watchful on the potential impact of intensified regulations on private sector confidence, and see if the existing government clari- fications are sufficient to restore market sentiment.

The salient shift of governance priorities from “growth first” to bal- anced growth and sustainability means that sectoral regulations will likely continue to be realigned with the broader goals of social equality and national security. We thus see potential new regulation and/or detailed implementation plans in the coming years for sectors associated with the rising tensions of income and wealth inequality, rapid fertility decline, environment, and national security risks amid post-Covid de-globalization.

That said, as aforementioned, we think these regulations are more about rebalancing the rise in corporate power and the share of labor compensation, and would not necessarily view them through the lens of “state vs. private”. Therefore, while we expect regulatory tightening on data-rich tech firms, platform companies, property developers to continue, sectors in-line with China's new economic agenda should continue to get support, such as semiconductor local- ization, cybersecurity software, innovative biotech and pharmaceu- tical companies with well-differentiated drugs, mass consumption/ domestic brands, vocational training, and green economy-related investment. For more equity investment analysis, please refer to

China Equity Strategy: Implications for Long-Term Valuation and ROE; Opportunities amid Headwinds & Tailwinds . Understanding China's Regulatory Reset Are there signposts to help us navigate the outlook based on past regulatory changes?

While China’s regulatory changes appear less transparent than western counterparts, we do observe similar cycles marked succes- sively by early warning signs, the formal process of drafting and releasing the regulatory documents, and official remarks signaling the end of the campaigns.

1. Early warning signs: These include increased social aware- ness/anxiety, public discussions, and meaningful deterioration in major macro level indicators, usually lasting 1-2 years (or possibly longer). For example, the latest crackdown on after- school tutoring followed top leaders’ negative assessment of the sector’s impact on children back in Sep-2018, but rapid growth continued, imposing a significant financial burden on middle income households. The antitrust campaign on tech giants was preceded by years of discussion over the contro- versy from "pick one from two" – a practice that came under the spotlight in 2015, which means platforms force merchants to have exclusive partnerships or distribution channels. Meanwhile, prominent macro-level regulatory campaigns include the financial cleanup since 2017 (following the five- year rapid rise in debt-to-GDP ratios) and capacity cuts in 2016-18 (following multiyear PPI deflation that further deep- ened in 2015).

3. Signs of reaching the final stages: For regulatory campaigns that have progressed relatively more smoothly, policymakers usually declare good results in high-level meetings – such as "decisive progress in the three critical battles against poverty, pollution and financial risk" at the 2021 NPC. On the other hand, for campaigns that brought about meaningful side effects, policymakers tended to soften their stance by, for example, calling for more market- or law-based implementa- tions (e.g., the latter stage of the supply side reforms). In rare cases when private sentiment was severely undermined on a broad scale, China's top leadership has reaffirmed its policy support with measures such as VAT cuts, lower social insur- ance payment ratio, better funding support, and further reforms and opening up.

Emergence of new norm following the regulatory shocks: Past experiences suggest that each regulatory wave tends to last for 1-2 years, during the start of which capital markets usually underper- formed amid rising risk premiums, but eventually the real economy and capital market adjusted to the new policy framework. As we argued above, most of the ongoing regulation (except for after- school tutoring) mainly focuses on striking a balance between the rise in corporate power and the share of labor compensation rather than aiming to revamp or terminate prevailing business models. In this sense, we believe the key signposts for an end to the current tech regulatory cycle could include:

1. A resumption of offshore IPOs by Chinese firms within less data-sensitive sub-sectors,

2. A systematic improvement in key digital platforms’ social ben- efit packages for flexible workers, and

3. Major fintech companies getting the greenlight for IPOs after fully complying with regulatory requirements.

Key policy risks to watch

We think the key risks lie mainly in China's endogenous growth momentum and external funding. First, while our base case assumes that policymakers can strike a balance between regulation and pri- vate sector vitality under the new policy framework, an inherent tendency to over-regulate could stifle private sector confidence and innovation. Second, a lack of sufficient communication and coordina- tion would not only disrupt business operations, but could also dis- courage foreign investment amid additional informational and cultural barriers. These could slow the pace of capital formation and undermine overall productivity growth in the economy.

Although some short-term pain arising from overdue regulation that follows a prolonged period of unregulated growth is inevitable, we see ways of mitigating the policy overhang.

1. A more anticipatory regulation framework and forward guid- ance for emerging industries could offer greater visibility and transparency, giving businesses sufficient time to adjust.

2. On policy coordination, regulatory policies would benefit from being pursued in an integrated manner in order to reduce trade-offs and maximize synergies. For example, it might be true that technology in the data era could boost growth, but it could also worsen income inequality, given its effect of favouring capital over labour and favouring skilled over unskilled labour. However, policymakers could narrow income disparities and help to defuse potential negative social impact by accelerating the urbanization 2.0 strategy and increasing fiscal transfers to optimize the social protection network.