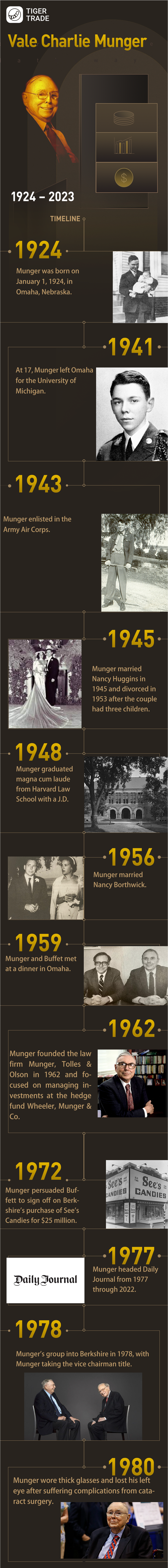

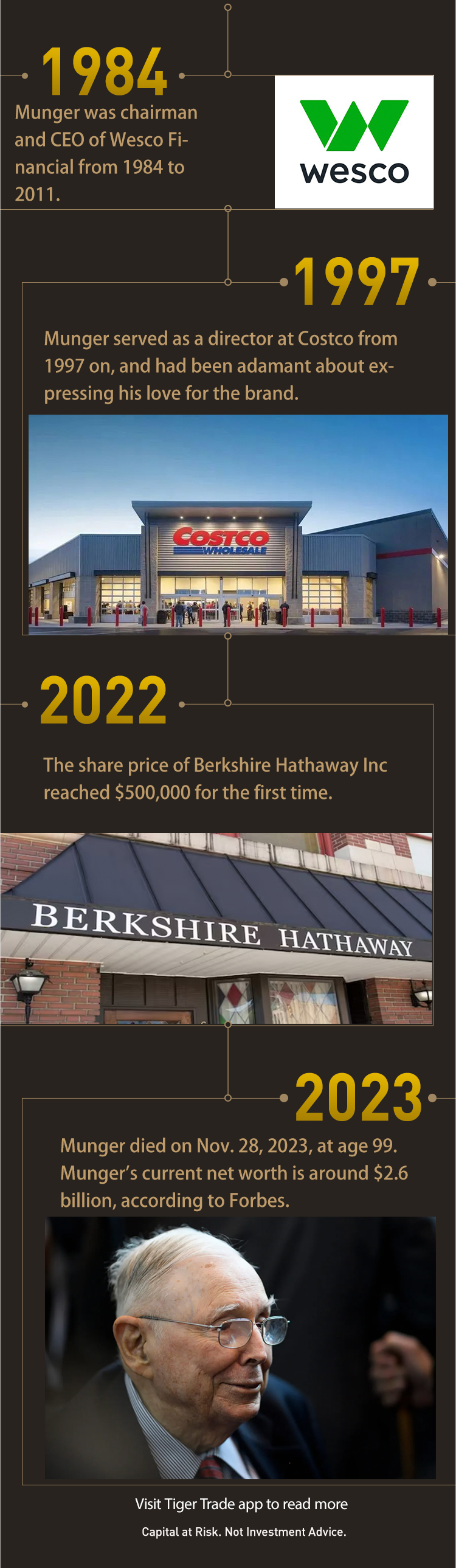

Charles Munger, the alter ego, sidekick and foil to Warren Buffett for almost 60 years as they transformed Berkshire Hathaway Inc. from a failing textile maker into an empire, has died. He was 99.

He died on Tuesday at a California hospital, the company said in a statement. He was a longtime resident of Los Angeles. “Berkshire Hathaway could not have been built to its present status without Charlie’s inspiration, wisdom and participation,” Buffett said in the statement.

A lawyer by training, Munger (rhymes with “hunger”) helped Buffett, who was seven years his junior, craft a philosophy of investing in companies for the long term. Under their management, Berkshire averaged an annual gain of 20% from 1965 through 2022 — roughly twice the pace of the S&P 500 Index. Decades of compounded returns made the pair billionaires and folk heroes to adoring investors.

Munger was vice chairman of Berkshire and one of its biggest shareholders, with stock valued at about $2.2 billion. His overall net worth was about $2.6 billion, according to Forbes.

At the company’s annual meetings in Omaha, Nebraska, where he and Buffett had both grown up, Munger was known for his roles as straight man and scold of corporate excesses. As Buffett’s fame and wealth grew — depending on Berkshire’s share price, he was on occasion the world’s richest man — Munger’s value as a reality check increased as well.

“It’s terrific to have a partner who will say, ‘You’re not thinking straight,’” Buffett said of Munger, seated next to him, at Berkshire’s 2002 meeting. (“It doesn’t happen very often,” Munger interjected.) Too many CEOs surround themselves with “a bunch of sycophants” disinclined to challenge their conclusions and biases, Buffett added.

For his part, Munger said Buffett benefited from having “a talking foil who knew something. And I think I’ve been very useful in that regard.”

Beyond Value

Buffett credited Munger with broadening his approach to investing beyond mentor Benjamin Graham’s insistence on buying stocks at a fraction of the value of their underlying assets. With Munger’s help, he began assembling the insurance, railroad, manufacturing and consumer goods conglomerate that posted nearly $29 billion of operating profit in the first nine months of this year.

“Charlie has always emphasized, ‘Let’s buy truly wonderful businesses,’” Buffett told the Omaha World-Herald in 1999.

That meant businesses with strong brands and pricing power. Munger nudged Buffett into acquiring California confectioner See’s Candies Inc. in 1972. The success of that deal — Buffett came to view See’s as “the prototype of a dream business” — inspired Berkshire’s $1 billion investment in Coca-Cola Co. stock 15 years later.

The acerbic Munger so often curbed Buffett’s enthusiasm that Buffett jokingly referred to him as “the abominable no-man.”

At Berkshire’s 2002 meeting, Buffett offered a three-minute answer to the question of whether the company might buy a cable company. Munger said he doubted one would be available for an acceptable price.

“At what price would you be comfortable?” Buffett asked.

“Probably at a lower price than you,” Munger parried.

Cardboard Cutout

From Los Angeles, Munger spoke frequently by phone with Buffett in Omaha. Even when they couldn’t connect, Buffett claimed he knew what Munger would think. When Munger missed a special meeting of Berkshire shareholders in 2010, Buffett brought a cardboard cutout of his partner on stage and mimicked Munger saying, “I couldn’t agree more.”

Munger was an outspoken critic of corporate misbehavior, faulting as “demented” and “immoral” the compensation packages given to some chief executives. He called Bitcoin “noxious poison,” defined cryptocurrency generally as “partly fraud and partly delusion” and warned that much of banking had become “gambling in drag.”

“I love his ability to just cut to the heart of things and not care how he says it,” said Cole Smead, CEO of Smead Capital Management, a longtime Berkshire investor. “In today’s society, that’s a really unique thing.”

Though Munger aligned with the US Republican Party, and Buffett sided with Democrats, the two often found common ground on issues like the desirability of universal health care and the need for government oversight of the financial system.

But while Buffett would tour the world urging billionaires to embrace charity, Munger said a private company like Costco Wholesale Corp. — he served on its board for more than two decades — did more good for society than big-name philanthropic foundations.

With his own donations, Munger promoted abortion rights and education. He served as chairman of Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles. Multimillion-dollar bequests to the University of Michigan and the University of California at Santa Barbara for new housing facilities gave him an opportunity to indulge a passion for architecture — though his vision for a 4,500-person dormitory on the Santa Barbara campus drew howls of protest in 2021 because the vast majority of bedrooms were to have no windows.

Wesco ‘Groupies’

Though he never rivaled Buffett in terms of worldwide celebrity, Munger’s blunt manner of speaking earned him a following in his own right.

He used the term “groupies” to refer to his fans, often numbering in the hundreds, who gathered to see him without Buffett. Hosting the annual meetings of Wesco Financial Corp., a Berkshire unit, in Pasadena, California, Munger expounded on his philosophy of life and investing.

At the 2011 meeting, the last before Berkshire took complete control of Wesco, Munger told his audience, “You all need a new cult hero.”

Charles Thomas Munger was born on Jan. 1, 1924, in Omaha, the first of three children of Alfred Munger and the former Florence Russell, who was known as Toody. His father, the son of a federal judge, had earned a law degree at Harvard University before returning to Omaha, where his clients included the Omaha World-Herald newspaper.

Munger’s initial brush with the Buffett family came through his work on Saturdays at Buffett & Son, the Omaha grocery store run by Ernest Buffett, Warren’s grandfather. But the two future partners wouldn’t meet until years later.

Munger entered the University of Michigan at age 17 with plans to study math, mostly because it came so easily. “When I was young I could get an A in any mathematics course without doing any work at all,” he said in a 2017 conversation at Michigan’s Ross Business School.

Nome to Harvard

In 1942, during his sophomore year, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps, soon to become the Air Force. He was sent to the California Institute of Technology to learn meteorology before being posted to Nome, Alaska. It was during this period, in 1945, that he married his first wife, Nancy Huggins.

Lacking an undergraduate degree, Munger applied to Harvard Law School before his Army discharge in 1946. He was admitted only after a family friend and former dean of the school intervened, according to Janet Lowe’s 2000 book, Damn Right! Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger. Munger worked on the Harvard Law Review and in 1948 was one of 12 in the class of 335 to graduate magna cum laude.

With his wife and their son, Teddy, Munger moved to California to join a Los Angeles law firm. They added two daughters to their family before divorcing in 1953. In 1956, Munger married Nancy Barry Borthwick, a mother of two, and over time they expanded their blended family by having four more children. (Teddy, Munger’s first-born, had died of leukemia in 1955.)

Not satisfied with the income potential of his legal career, Munger began working on construction projects and real estate deals. He founded a new law office, Munger, Tolles & Hills, and, in 1962, started an investment partnership, Wheeler, Munger & Co., modeled on the ones Buffett had set up with his earliest investors in Omaha.

“Like Warren, I had a considerable passion to get rich,” Munger told Roger Lowenstein for Buffett: The Making of an American Capitalist, published in 1995. “Not because I wanted Ferraris — I wanted independence. I desperately wanted it. I thought it was undignified to have to send invoices to other people.”

1959 Introduction

His fateful introduction to Buffett had come during a 1959 visit home to Omaha. Though the precise venue of their first meeting was the subject of lore, it was clear they hit it off right away. In short order they were talking on the telephone almost daily and investing in the same companies and securities.

Their investments in Berkshire Hathaway began in 1962, when the company made men’s suit linings at textile mills in Massachusetts. Buffett took a controlling stake in 1965. Though the mills closed, Berkshire stuck around as the corporate vehicle for Buffett’s growing conglomerate of companies.

A crucial joint discovery was a company called Blue Chip Stamps, which ran popular redemption games offered by grocers and other retailers. Because stores paid for the stamps up front, and prizes were redeemed much later, Blue Chip at any given time was sitting on a stack of money, much like a bank does.

Using that pool of capital, Buffett and Munger bought controlling shares in See’s Candies, the Buffalo Evening News and Wesco Financial, the company Munger would lead.

In 1975, the US Securities and Exchange Commission alleged that Blue Chip Stamps had manipulated the price of Wesco because Buffett and Munger had persuaded its management to drop a merger plan. Blue Chip resolved the dispute by agreeing to pay former investors in Wesco a total of about $115,000, with no admission of guilt.

The ordeal underscored the risks in Buffett and Munger having such complicated and overlapping financial interests. A years-long effort to simplify matters culminated in 1983 with Blue Chip Stamps merging into Berkshire. Munger, whose Berkshire stake rose to 2%, became Buffett’s vice chairman.

China Bull

In recent years, Munger’s fans continued to travel to Los Angeles to ask him questions at annual meetings of Daily Journal Corp., a publishing company he led as chairman. He displayed his knack for investing by plowing the company’s money into temporarily beaten-down stocks like Wells Fargo & Co. during the depths of the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

Munger was for many years more bullish than Buffett when it came to investing in China. Berkshire became the biggest shareholder of Chinese automaker BYD Co., for instance, years after Munger began buying its stock, though Berkshire began trimming that stake in 2022.

Munger started sharing his vice chairman title at Berkshire in 2018 with two next-generation senior executives, Greg Abel and Ajit Jain, who were named to the board in a long-awaited sign of Buffett’s succession plans. Buffett subsequently identified Abel as his likely successor.

It was Munger who, three years earlier, had signaled the likely promotion of Abel and Jain with praise delivered in his signature fashion: with a backhanded swipe at the boss.

“In some important ways,” he wrote of the pair in 2015, “each is a better business executive than Buffett.”