Learn the basics of covered calls and covered puts, and when to use them to manage your risks when trading options.

When employed correctly, covered calls and covered puts can help manage risk by potentially increasing profits and reducing losses simultaneously. Let's discuss how.

What is a covered call?

A covered call is when you sell someone else the right to purchase shares of a stock that you already own (hence "covered"), at a specified price (strike price), at any time on or before a specified date (expiration date). The payment you receive in exchange is called a premium, which you keep regardless of whether the call is exercised.

As a result, covered calls can help generate income in a flat or mildly uptrending market. If the price of the underlying stock rises above the call option's strike price, the covered call buyer can exercise their right to purchase the stock, and you would relinquish any gains on the underlying stock above the strike price. However, the premium you received offsets some of the risk of foregone profits—as well as some of the risk of a small decline.

In fact, the best-case-scenario for this strategy would be the stock price rising slightly, giving you both a modest gain from stock price appreciation and some premium income from the call.

When do you use a covered call?

Investors typically write covered calls when they have a neutral to slightly bullish sentiment on the underlying stock. In many cases, the best time to sell covered calls is either at the same time you establish a long equity position (known as a "buy/write"), or once the equity position has already begun to move in your favor.

When establishing a covered call position, most investors sell options with a strike price that is at-the-money (or ATM, meaning the option’s strike price is the same as the stock's current market price) or slightly out-of-the-money (or OTM, meaning the strike price is above the stock’s current market price). If you write an OTM or ATM covered call and the stock remains flat or declines in value, you’re hoping the option eventually expire worthless, and you get to keep the premium you received without further obligation.

If the stock price rises above the option's strike price, it’s likely your stock will be called away (assigned) at the strike price, either prior to or at expiration. This is usually a good thing. If you sold ATM or OTM calls, the trade will generally be profitable. In fact, your profit will usually exceed what you would have earned if you had simply bought the stock and then sold it at the appreciated price, as you would receive both the proceeds from the sale of the stock at the strike price and the option premium.

That said, if the stock rises significantly, leaving the options deep in-the-money (or ITM, meaning the stock's market price is above the option’s strike price), the stock investment on its own would have been better.

Here's a hypothetical example of a covered call trade. Let's assume you:

- Buy 1,000 shares of XYZ stock @ $72 per share

- Sell 10 XYZ Apr 75 calls @ $2.00 (Note that each standard call or put generally represents 100 shares of the underlying stock, thus, the 1,000 shares "cover" the 10 calls sold).

The two points provided by the covered call create some immediate downside protection because you wouldn't experience a loss on the position unless the stock you bought for $72 a share dropped below $70. Another way to think of it is that even if the stock price dropped to zero, you would still have $2,000 from the 10 covered calls you sold (that is: $2 x 10 covered calls x the option multiplier of 100).

The trade-off is that you would effectively cap your potential profit if the share price rose significantly above the strike price. For this trade, that would mean a maximum profit of $5,000, representing the sum of your capital gain from the stock appreciating up to the $75 strike price and your premium from the covered call (that is: $3 x 1,000 shares of stock + $2 x 10 options contracts x 100 options multiplier). In that sense, this trade would make sense only if you thought it unlikely the price of XYZ would exceed $77 by the April expiration (representing the sum of your $72 purchase price and your max profit of $5,000). If XYZ did increase above $77, it would have been more profitable not to have written the covered call.

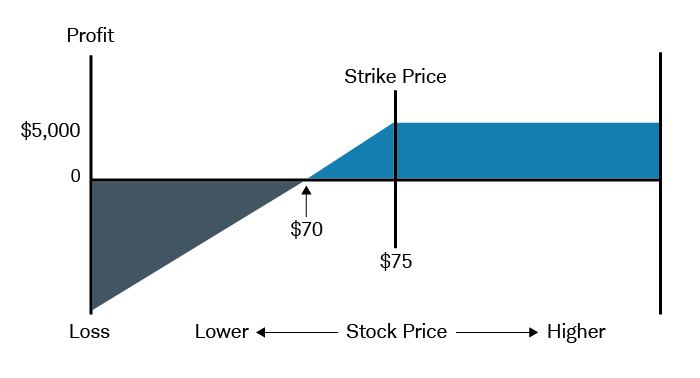

As you can see in the profit and loss chart below:

- The breakeven price is $70.

- The profit is capped at $5,000 for all prices above $75.

- Losses will be incurred below $70; down to zero.

What is a covered put?

Covered puts work essentially the same way as covered calls, except that you're writing an option against a short position, meaning a stock you've borrowed and then sold on the open market. Whereas writing a covered call involves selling someone else the right to buy a stock you own, selling covered puts against a short equity position creates an obligation for you to buy the stock back at the strike price of the put option.

This strategy typically makes sense when you have a neutral to slightly bearish sentiment.

As with covered calls, you can sell covered puts either when you establish the position (called a "sell/write"), or once the short equity position has already begun to move in your favor.

Here's an example of a covered put trade. Let's assume you:

- Sell short 1000 shares of XYZ @ 72

- Sell 10 XYZ Apr 70 puts @ 2

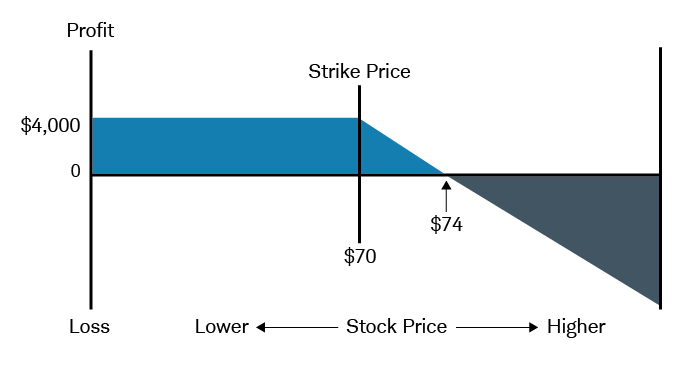

In the chart below, you'll see that:

- The breakeven price is $74.

- The profit is capped at $4,000 for all prices below 70, i.e.: $2 x 1,000 [shares of stock] + $2 x 10 [options contracts] x 100 [options multiplier]

- Losses will be incurred above $74.

You would want to employ this strategy only if you thought the price of XYZ wouldn't fall below $70 by the April expiration. If XYZ did fall below $70, the short stock trade alone would be more profitable. Losses are potentially unlimited if the stock price continued to increase, but they would always be $2,000 less than the stock trade alone.

Risk managed, not eliminated

While covered calls and covered puts can reduce risk somewhat, they cannot eliminate it entirely. With that in mind, here are a few cautionary points about these strategies:

- Profits. Covered options usually limit your profit potential if a stock moves substantially in your favor. Anytime you sell a covered option, you have established a minimum buying price (covered put) or maximum selling price (covered call) for your stock. Any stock movement beyond that established price creates no additional profit for you.

- Losses. Losses are reduced only by the amount of premium you received on the initial sale of the option. In addition, it’s rarely a good idea to sell a covered option if your stock position has already moved significantly against you. Doing so could cause you to establish a closing price that ensures a loss. So, before you sell, ask yourself, "Would I be happy if I had to close out my stock position at the strike price on this option?" If you can answer "yes," you’ll probably be okay.

- Holding until expiration. While our examples assume that you hold the covered position until expiration, you can usually close out a covered option at any time by buying it to close at the current market price. Regardless of whether the equity part of your strategy is profitable, waiting until expiration will maximize your return on an out-of-the-money option; however, you are not required to do so.

- Assignment. A significant change in the price of the underlying stock prior to expiration could result in an early assignment, and if your short option is in-the-money, you could be assigned at any time. Covered calls written against dividend paying stocks are especially vulnerable to early assignment.

- Corporate events. When companies merge, spin off, split, pay special dividends, etc., their options can become very complicated.