The Federal Reserve on Wednesday decided against what would have been an 11th consecutive interest rate increase as it measures what the impacts have been from the previous 10.

But the decision by the Federal Open Market Committee to hold off on a hike at this meeting came with a projection that another two quarter percentage point moves are on the way before the end of the year.

Central bankers following a two-day meeting said they will take another six weeks to see the impacts of policy moves as the Fed fights an inflation battle that lately has shown some promising if uneven signs. The decision left the Fed’s key borrowing rate in a target range of 5%-5.25%.

“Holding the target range steady at this meeting allows the Committee to assess additional information and its implications for monetary policy,” the post-meeting statement said. The Fed next meets July 25-26.

Markets had widely been anticipating the Fed to “skip” this meeting – officials generally prefer the term to a “pause” that infers a longer-range plan to keep rates where they are. The expectation leaned heavily against an increase after policymakers, particularly Chairman Jerome Powell and Vice Chair Philip Jefferson, had indicated that some change in approach could be in order.

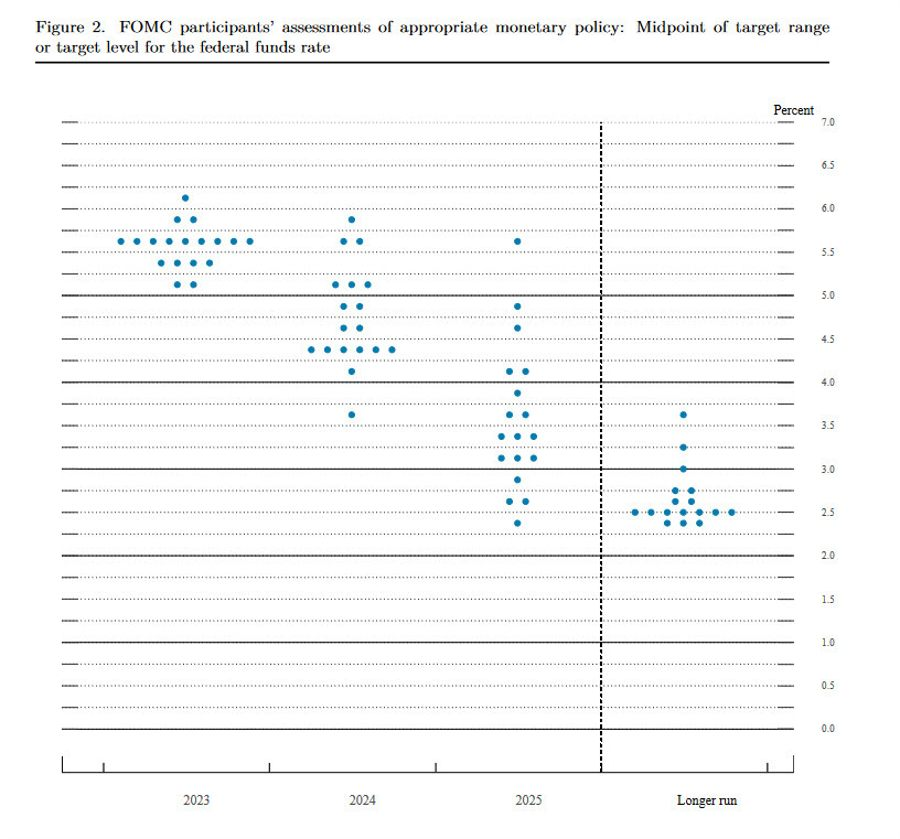

The surprising aspect of the decision came with the “dot plot” in which the individual members of the Federal Open Market Committee indicate their expectations for rates further out.

The dots moved decidedly upward, pushing the median expectation to a funds rate of 5.6% by the end of 2023. Assuming the committee moves in quarter-point increments, that would imply two more hikes over the remaining four meetings this year.

FOMC members approved Wednesday’s move unanimously, though there remained considerable disagreement among members. Two members indicated they don’t see hikes this year while four saw one increase and nine, or half the committee, expect two. Two more members added a third hike while one saw four more, again assuming quarter-point moves.

Members also moved up their forecasts for future years, now anticipating a fed funds rate of 4.6% in 2024 and 3.4% in 2025. That’s up from respective forecasts of 4.3% and 3.1% in March, when the Summary of Economic Projections was last updated.

The future-year readings, though, do imply the Fed will start cutting rates – by a full percentage point in 2024, if this year’s outlook holds. The long-run expectation for the fed funds rate held at 2.5%.

Those changes to the rate outlook occurred as members raised their expectations for economic growth, now anticipating a 1% gain in GDP as compared to the 0.4% estimate in March. Officials also were more optimistic about unemployment, now seeing a 4.1% rate by year’s end compared to 4.5% in March.

On inflation, they raised their collective projection to 3.9% for core (excluding food and energy) and lowered it slightly to 3.2% for headline. Those numbers had been 3.6% and 3.3% respectively for the personal consumption expenditures price index, the central bank’s preferred inflation gauge. The outlook for subsequent years in GDP, unemployment and inflation were little changed.

Fed officials believe that policy moves work with “long and variable lags,” meaning it takes time for rate hikes to work their way through the economy.

The Fed began hiking rates in March 2022, about a year after inflation started a dramatic climb to its highest level in some 41 years. Those rate hikes have amounted to 5 percentage points on the Fed’s benchmark to a level not seen since 2007.

The hikes have helped push 30-year mortgage rates over 7% and also spiked borrowing costs for other consumer items such as auto loans and credit cards.

Recent data points such as the consumer and producer price indexes have shown the rate of inflation slowing, though consumers still face high costs for many items. The FOMC statement continued to note that “inflation remains elevated.“

Inflation hit the U.S. economy due to multiple pandemic-related factors – clogged supply chains, unusually strong demand for high-priced goods over services, and trillions in stimulus from both Congress and the Fed that had an abundance of money chasing a dearth of goods.

At the same, supply/demand mismatches in the labor market had pushed both wages and prices higher, a situation the Fed has sought to correct through policy tightening that has included both rate increases and a reduction of more than half a trillion dollars from the assets it holds on its balance sheet.