Clients say 'markets don't feel right,' one markets research analyst notes

Peter Andersen, a Boston-based money manager, started 2021 feeling upbeat.

"I think this is going to be one of the historic recoveries, up there with the end of major wars," he told MarketWatch around the turn of the year. "There's enormous demand from consumers. Can you imagine when we get the all-clear and start moving back toward normalcy?"

But three months into the year, Andersen is glum. In an interview last week, he talked about the way big segments of the market seem to be in favor one day, out the next. "We toggle between value and growth, stay-at-home and re-opening, almost daily," he said. "I don't know who is driving this, but it must be following some kind of algorithm."

Andersen is trying to be patient, recognizing that the economy is at a once-in-a-generation inflection point and that everyone is operating in unprecedented conditions. Still, he said, the financial markets sometimes feel like a house of cards.

"It's confounding," he said. "The market is fragile, and surprisingly so. This whole year for me has been really challenging to try to figure out is there any momentum, what direction is it going in and what's responsible for it."

As if the horrors of the global coronavirus pandemic weren't enough of a curveball, the past 12 months have thrown up a slew of other headwinds against smooth market sailing. There's the surge of retail traders bent on using the stock market as a gambling casino , and a national politics so bitter that the presidential election turned bloody.

And that's not even counting the more existential questions: what's the right level for a stock market that plunged 33% in about two weeks just a year ago? How much of that gain comes down to policy stimulus and how much is real? How much of the expected economic rebound is already priced in? What happens if the vaccine promise falls short? What if this is as good as it gets?

Taken together, it leaves people who manage money, their clients, and the companies that advise them, just as befuddled as Andersen, with almost as many perceived red flags as there are theories as to what's causing it all.

"The most common observation we get from clients is that markets don't "feel right", and we absolutely get that," wrote Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research, in a recent note. "For us, a big piece of this unease comes from the novelty of seeing capital markets go from distress to euphoria in such a short period of time."

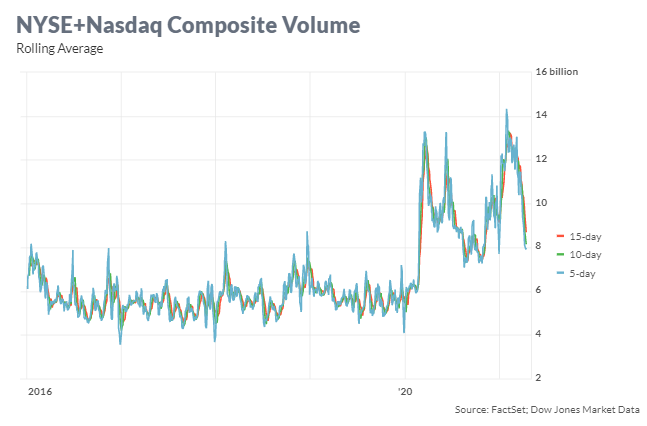

Market observers point to all manner of weird quirks that seem to confirm something is askew. Among other things, trading volumes have plunged to start 2021.

To be sure, the elevated volumes in 2020 were just that -- an outlier. But by some estimates, inexperienced amateur traders now make up as much as 20% of all volume in the markets. And even if all of them aren't out gunning for short-sellers, they still have very different priorities and incentives than much of the rest of the market.

Also unsettling was the spike U.S. Treasury yields in only a few weeks in the first quarter this year, spooking stock-market investors, followed by several weeks of Federal Reserve policymakers reassuring markets that any interest rate rises wouldn't start until 2023 and would be telegraphed well in advance. Strangely then, rosy economic data seemingly caused bond yields to plunge in mid-April.

"Other weird stuff is going on," mused Evercore ISI's Dennis DeBusschere, in a note attempting to explain the government-bond rally. "SPAC's and Solar are getting hit hard on a relative basis, which is odd given the move lower in 10 year yields. Some are citing that the retail investor-sponsored names are getting hit in general as they move away from the market. And why are homebuilders underperforming with 10 year yields collapsing?"

Dave Nadig is a long-time student of market structure, including as one of the first developers of exchange-traded funds to help markets avoid another blow-up like 1987's Black Monday.

Nadig thinks markets are healthy -- that is, working efficiently and staying resilient, even through hiccups like the meme-stock rampage in the past couple of months and the Archegos family office blow-up. What's become "very fragile," in his words, is price discovery.

"There are some fundamental underpinnings of how markets work that are dissolving," he said in an interview. "What we're realizing is that there's a lot more noise and randomness in the market than people are willing to admit. Mostly what's changed is information flow and data moving faster and faster. Any model you build today by definition fails to take into account an acceleration tomorrow."

Take the Gamestop Corp. $(GME)$frenzy that erupted in January . After a group of disgruntled traders spent several weeks targeting short sellers by driving the price of that stock higher, "It's no longer a normal stock -- it's an externality in the market that has ripple effects some investors may not even be aware of," Nadig said.

Older investing models -- and algorithms -- are bumping up against new ones that take into account new conditions, a process Nadig calls "an arms race," and one that's accelerated because of the modern speed of information flow and reaction functions.

"We're starting to see cracks in the traditional ways we've always analyzed markets," he said. "We're no longer processing reality, we're processing information, and it gets priced in instantaneously. We've given up on analyzing."

That means that a headline, say, about a pause in the use of Johnson & Johnson's COVID-19 vaccine shares trade lower, Nadig said. It means that for that day, the entire "re-opening" trade -- and by extension, some cyclical trades and some value plays -- suffers.

For Peter Andersen, who's managed money for nearly three decades and returned more than 40% for his clients in each of the the past two years, the market's fragility is frustrating. Andersen prides himself on "fierce independence" in stock selection that results in a macro-agnostic portfolio. Some of his recent investments have been in cybersecurity, data storage, and pet care.

In the year to date, however, one of Andersen's top picks, Trupanion Inc. (TRUP), is down 33%, for no logical reason, he noted. "It's as if someone thinks everyone is going to euthanize their pets!"

Stocks looked past the Johnson & Johnson news to close higher for the week with both the Dow and S&P500 index at new records. The Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 1.2%, the S&P 500 was up 1.4%, and the Nasdaq Composite added 1.1%.

The coming week will bring U.S. economic data on the housing market, including existing- and new- home sales, and a raft of corporate earnings reports.