Inflation likely continues to cool. Lots of Americans are still experiencing sticker shock.

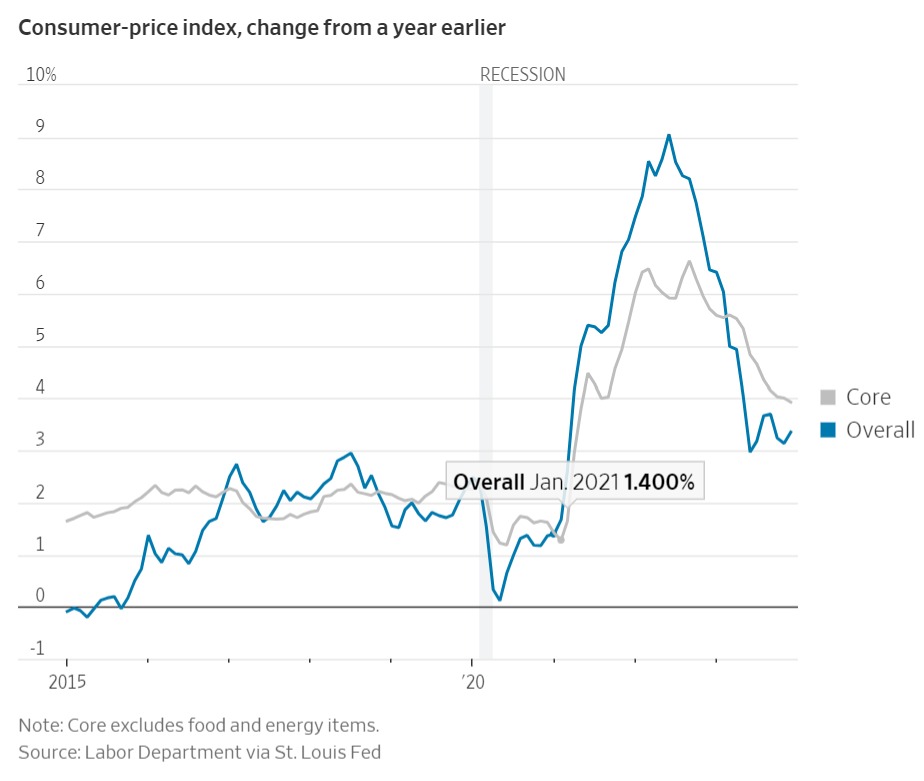

Economists polled by The Wall Street Journal expect the Labor Department's monthly inflation report will show that overall consumer prices were up 2.9% in January from a year earlier. That would mark the smallest gain since March 2021.

They estimate that core prices, which exclude food and energy items in an effort to better track inflation's underlying trend, were up 3.7%, for the slimmest gain since April 2021.

The report is set for release Tuesday at 8:30 a.m. Eastern time.

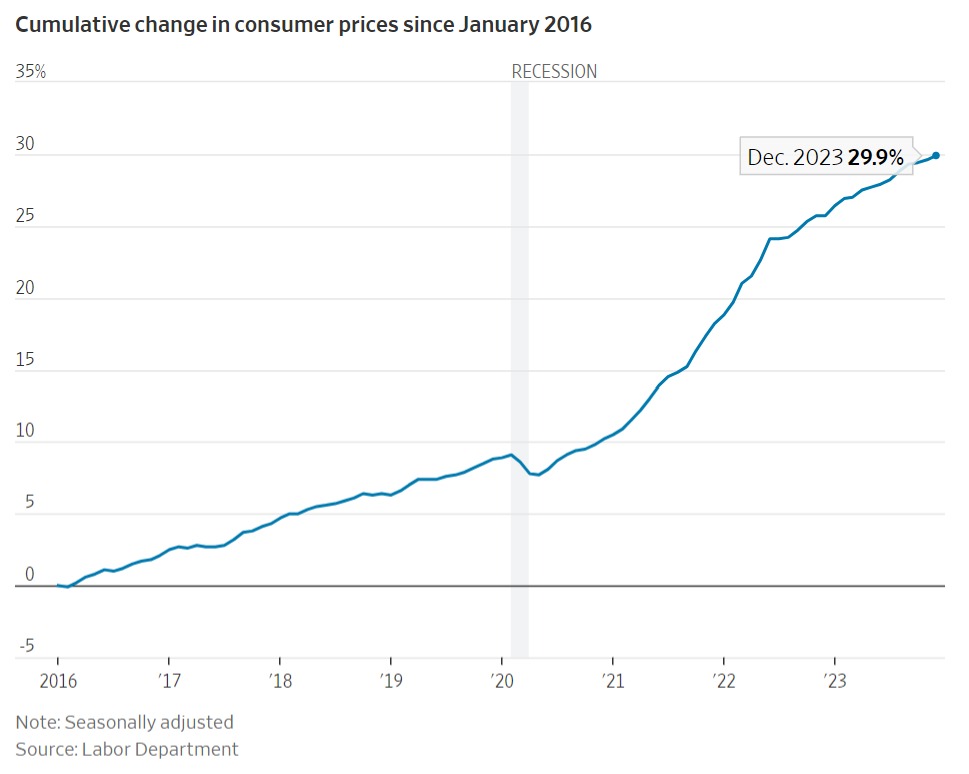

But prices are still far above where they were before the pandemic, especially for goods that most Americans buy often, such as groceries.

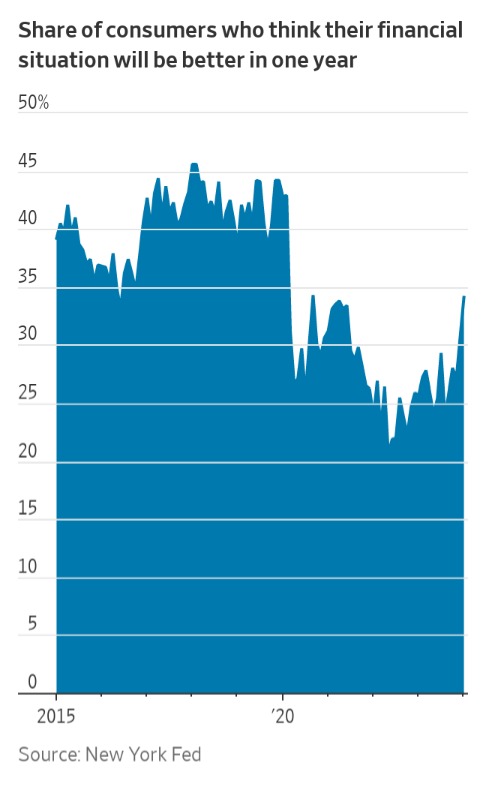

The sting of those past price increases might be part of why so many Americans remain down on the economy. An analysis conducted by Goldman Sachs economists suggests that frustration with high price levels might have contributed to low confidence readings that persisted in the early 1980s even after inflation had slipped sharply.

"It does seem like it takes a while for confidence to recover, in part because people are focused on levels rather than changes," said Goldman chief economist Jan Hatzius.

Recent monthly readings have been running cooler than a year ago, and economists expect that continued in January. They estimate that overall prices were up a seasonally adjusted 0.2% from the prior month, and core prices up 0.3%.

The Federal Reserve's preferred measure of inflation, from the Commerce Department, will come out later this month, and it has been running lower than the Labor Department's. But even allowing for that fact, inflation last month was likely still running above the 2% that the central bank is aiming for.

Economists generally expect inflation to cool this year, though they caution that the process could be bumpy. The unwinding of supply-chain problems has helped subdue the prices for many goods, for example, while used-car prices, which were a major source of inflation shortly after the pandemic struck, have lately been falling. New rent prices have also cooled over the past year, as seen in data from private providers as well as a new tenant rent index from the Labor Department.

On the other hand, inflation in some services prices could prove sticky, cautions Morgan Stanley economist Diego Anzoategui, and that could put upward pressure on month-to-month price readings. "We think that especially in the first quarter of the year, inflation is going to be slightly higher than what we've seen in the past six months," he said. "In the second half of the year, we are expecting more disinflation on the services front."

Fed officials, too, think that inflation has probably been contained, and that is a big part of why they expect to cut rates later this year. "So we have six months of good inflation data," said Fed Chair Jerome Powell at the news conference following the central bank's policy-setting meeting two weeks ago.

But, he added, Fed officials want to see more evidence that "confirms what we think we're seeing and...gives us confidence that we're on a path to, a sustainable path down to 2% inflation."

Although prices are no longer rising as quickly as they were a year ago -- and in some cases are even falling -- they are still well above where they were before the pandemic. Economists' forecasts imply the Labor Department's measure of overall consumer prices was up 19.3% this January from four years earlier, just before the pandemic hit. In contrast, prices were up 8.9% in the four years ended January 2020.

Some of the pessimism on the economy appears to be fading. The New York Fed on Monday reported that the share of respondents in its monthly survey of consumers who thought their household's financial situation would be better in a year rose to 34.1% in January from 30.6% in December, marking the highest level since September 2020. The survey also showed that consumers expect prices to rise 3% over the next year -- the lowest that figure has been since December 2020.

"I can tell inflation has gotten better," said Mike Poore, of Henderson, Ky. "That's definitely a good thing. It's a shame it's not happening quicker."

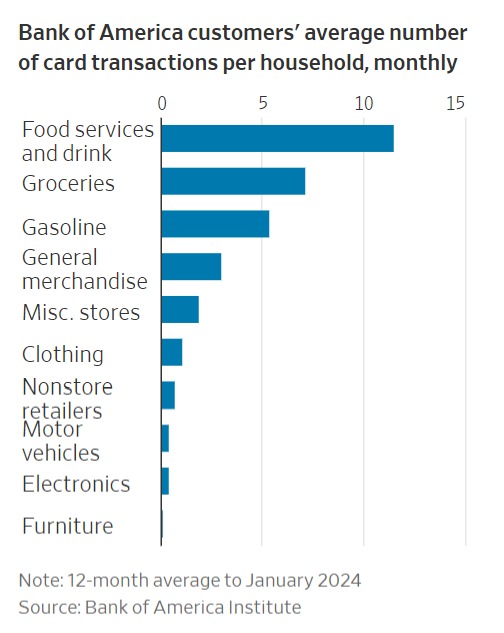

Another reason why people might see less progress on inflation than the official figures suggest is that the prices for some of the things they buy the most frequently have risen by a lot since the pandemic hit. A Bank of America Institute analysis of customer data found households tended to make far more transactions a month for food and drinks at restaurants and bars, for groceries and for gasoline than they do for other items. Labor Department figures show that prices in all three of those frequent-transaction categories are higher, relative to before the pandemic, than prices overall.

Research from University of California, Berkeley, economist Ulrike Malmendier and three co-authors found that prices for items that people buy more often play an outsize role in framing their inflation expectations. "In terms of what gets ingrained in people's brains, it's stuff that they purchase frequently," she said.

Other research that Malmendier has conducted examines the scarring effects of inflation episodes, which can have persistent, and potentially costly, effects on people's financial decisions. She is heartened by the fact that inflation has retreated relatively quickly from the 9.1% it hit in June 2022 -- a contrast to the experience of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when inflation remained elevated for years.

"I'm a little less worried about long-lasting effects than I was in 2022," she said.