At his 60th birthday party in a New York City hotel, David Gottesman was surrounded by a few dozen family members and dear friends, the people close enough to the Wall Street investor to call him Sandy. By his side that night was his wife, Ruth, a pioneering researcher at a Bronx medical school. A highlight of the evening came when the man who would be responsible for much of their wealth raised his glass.

"May you live till Berkshire splits," toasted Warren Buffett.

By then, Gottesman was not just one of Buffett's close friends and confidants but a significant shareholder in Berkshire Hathaway. He acquired his shares when an early business venture with Buffett and partner Charlie Munger merged with Berkshire in the 1970s. That turned out to be a billion-dollar development, as Berkshire's shares delivered a fortune to early investors.

Buffett never split Berkshire's original Class A shares and Gottesman lived until he was 96 years old. When he died in 2022, he left stock to Ruth and told her to do with it whatever she thought was right.

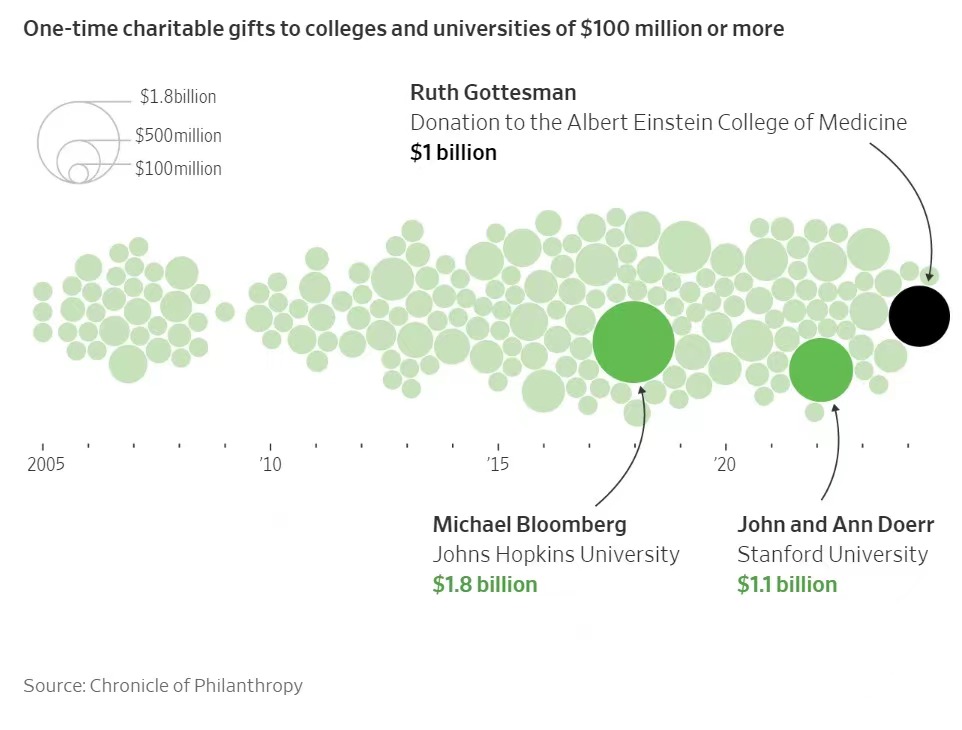

What she did captured the world's attention. She decided it would be right to donate $1 billion to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine to cover the tuition of every student in perpetuity, ensuring the school's future doctors will no longer have to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for their medical education.

Her extraordinary gift announced this past week was decades in the making. Ruth Gottesman, 93, joined the Einstein faculty in 1968, not long after her late husband met Buffett. Their friendship led to a business partnership, an epic investment and, now, a tuition-free medical school.

"I've never seen anybody behave better with a billion dollars," Buffett said when reached by phone this past week.

The Gottesmans were among the friends and partners of Buffett who watched their early Berkshire investments compound over decades into millions and sometimes billions of dollars. Berkshire's Class A shares now trade above $600,000 apiece, up from roughly $150 when Gottesman acquired his stock through a merger. The company's Class B shares were rolled out in 1996 and trade around $400.

Buffett and Ruth Gottesman remain in touch to this day, and she told him of her plans to make this $1 billion gift, which instantly elevated a low-profile nonagenarian educator into the ranks of the world's leading philanthropists.

Philanthropy in the family

Ruth Levy grew up in Baltimore as one of four daughters. Her father ran a family business manufacturing straw hats and built a monumental collection of American sheet music, including a rare first edition of "The Star-Spangled Banner." Her mother was a homemaker who also worked for the city's welfare department and an adoption agency for Black children. Philanthropy was in Ruth's blood. Before she was born, her parents were among the founders of a scholarship program for Maryland high-school students that still exists today. One of the formative moments of Ruth's life came when she was around 10 years old and her family took in another 10-year-old girl fleeing Nazi Germany during World War II.

"She never said goodbye to her parents and she didn't know whether they would be alive after the war," Ruth Gottesman once said. "That began a process of seeing others and feeling their pain."

When she graduated from Barnard College in 1952, Ruth had a hard time finding a job that suited her. She briefly worked as an assistant editor at a food magazine and gave secretarial school a whirl, but neither stuck. "I flunked shorthand," she said. She enrolled at Columbia University's Teachers College, where she received a master's degree and then a doctorate in educational psychology. In 1968, she joined the Children's Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center at Einstein, where she developed evaluation and treatment programs for children with learning disabilities and started a program for adult literacy.

Meanwhile, she met Sandy Gottesman in 1948 and they married in 1950, when he graduated from business school and went to work on Wall Street. Early in his career, he began to hear about a guy in Omaha, Neb., who was similarly obsessed with buying undervalued stocks.

His name was Warren Buffett.

They met in 1962 and kept talking for the next 60 years.

"From then on," Sandy Gottesman once said, "it was a complete romance."

During a visit Gottesman made to Omaha to see Buffett, they began chatting in the afternoon and holed up in Buffett's office until 3 a.m. When they tried to leave, they discovered that the building's elevator bank had been gated off from its entrance. They were locked in the building until they found someone to let them out. "It wouldn't have bothered us if we couldn't have gotten out," Buffett says today. When they couldn't talk in person, they spoke by phone on Sundays. By the time they hung up around midnight, Gottesman felt like he'd chugged a double espresso. "I was so stirred up and so excited I didn't go to sleep for a couple of hours," he said.

(Gottesman rarely spoke with the media, but he made an exception to discuss Buffett. Most of his comments in this article were taken from a 2016 interview with filmmaker Peter Kunhardt, who directed the HBO documentary "Becoming Warren Buffett.")

Their personal friendship turned into a professional relationship by 1966, when Buffett was looking for companies to buy and Gottesman called him with an idea: What about buying a department store in Baltimore?

As it happened, the department store Hochschild Kohn was run by Ruth's extended family (her mother was a Kohn), and Sandy knew they were ready to sell. Buffett, Munger and Gottesman formed a company called Diversified Retailing and bought it.

It soon became clear they had made a big mistake.

"We had a lemon on our hands," Buffett says.

Munger once put it another way: "Buying Hochschild Kohn was like the story of a man who buys a yacht: The two happy days are the day he buys it and the day he sells it."

It was an especially happy day when Gottesman was able to resell the department store for only a minimal loss. They eventually turned a lemon into lemonade. The three partners merged Diversified, which by then owned a separate chain of women's clothing stores, into Berkshire at the end of 1978, handing Diversified stockholders a golden ticket: shares of Berkshire.

Over the years, Buffett acquired businesses from See's Candies to insurer Geico and placed successful bets on stocks like Apple, Coca-Cola and American Express, propelling Berkshire's growth into one of the most valuable U.S. companies.

Since the Diversified merger, Berkshire's stock has soared more than 400,000%, compared with the S&P 500's total return of roughly 18,000%.

'Very, very, very bright'

Gottesman and Buffett's friendship lasted much longer than their ownership of the department store. "We never had an argument or even a disagreement of any kind, and we were in a lousy business together to start," Buffett says. The one area where they couldn't agree was how they met. Gottesman always said that a mutual friend introduced them for lunch. Buffett insists they were supposed to play golf, which he remembers because his back gave out when he reached for his wallet to pay for gas on his way to the course. He thought about canceling, but he kept driving to meet Gottesman.

"Not only did I become a good friend of Sandy's, but our wives became very good friends, and the families became friends with each other," Buffett says.

Buffett's first wife, Susie, was a singer. Ruth accompanied her on piano. When the Buffetts traveled to New York after the Berkshire annual meeting, they would end their trip with a visit to the Gottesmans, who called the part of their Rye, N.Y., house where their guests from Nebraska stayed "the Buffett wing."

During one of those afternoons at the Gottesman home, Ruth shyly mentioned that she had just received her doctorate. Buffett knew she was "very, very, very bright," he says, but he was impressed by her modesty. He told her that if he had gotten a doctorate, he would have bought a full-page ad in the newspaper. "Ruth never wants to draw attention to herself," he said. "She just isn't that sort of person."

Sandy Gottesman was the same way. He was elected to Berkshire's board in 2003 and remained a director until his death in 2022. But he spent most of his life allergic to publicity, almost never speaking with the press or explaining the decisions of First Manhattan, the investment company he founded in 1964 that manages more than $20 billion today. He said there was a reason he chose to remain under the radar. "The only time a whale gets harpooned is when he surfaces," he said in an interview for his New York Times obituary.

'The results have been spectacular'

Ruth Gottesman kept busy after she retired as a professor emerita in 2001, joining Einstein's board of trustees, serving as chair from 2007 to 2014 and returning to that leadership role in 2020.

She took some time after Sandy's death before she came up with an idea for how to use the Berkshire stock he left to her: to make Einstein tuition-free.

Einstein charges more than $60,000 a year in tuition, but living expenses bring the annual price of attending the four-year medical school in New York closer to $100,000. By making it more affordable, she's hoping to make it more accessible.

The Gottesmans were already major donors whose name can be found on institutions from the American Museum of Natural History to the Israel Aquarium. Ruth and Sandy also gave $25 million in 2008 to Einstein and had a research institute and teaching center named after them there.

But for one of the largest philanthropic contributions in the history of U.S. higher education, Gottesman wished to remain anonymous before she was persuaded to attach her name to the billion-dollar gift. When she agreed to be recognized, she made an unusual request: She asked that Einstein not be renamed in her honor. Since then, Gottesman has shied away from the spotlight, turning down media requests after granting an interview to the New York Times to explain her donation.

She declined to comment for this article.

Her lone appearance was in a packed auditorium on Monday morning at Einstein, where students assembled with no idea why they had been called to a mandatory meeting. The future doctors screamed, jumped out of their seats and cried when Gottesman made her announcement.

Buffett wrote in a 2023 letter to shareholders of the pleasure that he and Munger, who died in November, took from watching “the vast flow of Berkshire-generated funds” to satisfying public needs, rather than “look-at-me assets and dynasty building.” Buffett pledged in 2006 to donate all of his Berkshire shares to philanthropy and said in 2021 that he was halfway there. His remaining shares, according to a November filing, are now worth around $130 billion.

In his letter, Buffett highlighted the Berkshire investors who eventually give much of their money to philanthropic organizations which then work to “improve the lives of a great many people who are unrelated to the original benefactor.”

“Sometimes,” he wrote, “the results have been spectacular.”

Ruth Gottesman’s gift was one of those times.

“She could change all these people’s lives by giving up something that wasn’t actually important to her and would be hugely important to thousands of people over time,” Buffett said this past week.

Ruth has said that she thinks and hopes Sandy would be pleased by her decision. He once said that the Berkshire investment allowed the Gottesmans to make charitable gifts “that have brought joy to the whole family,” for which he owed Buffett more than a toast.

“He’s had an enormous influence on my life,” he said, “and my wife’s life.”